[continued from part V]

Relay attacks are not new: they were originally introduced in the context of RFID systems and smart-cards. As soon as mobile devices gained NFC capability, it seemed a foregone conclusion that this class of vulnerabilities would apply. The phone may have a different form factor, but abstract threat model is unchanged. If anything the situation got worse because of an added twist: because the “card” was effectively “attached” to a generic computing device, physical proximity to the victim is no longer required. If the attacker could execute code on the mobile device, that malware could relay their commands over a network link remotely.

Earlier defenses against relay attacks focused on distance-bounding, by measuring time taken for the gadget to respond to specific “challenge” commands. Excessive delays can be interpreted as evidence that traffic is being relayed over a long distance with network hops in between. This is at best an unreliable approach since it is betting on the network latency between victim and attacker. With improving networking technologies, it may become more difficult to identify a sharp threshold for differentiating between local and remote cases.

Fortunately modern dual-interface chips such as the Android secure element has a more robust and reliable mitigation: interface detection. Unlike the simplistic descriptions of relay attacks which posit a single communication path to the chip, there are in fact two distinct routes or interfaces. More importantly applications running on these chips can detect which route a particular message came from. This is an intrinsic property of the hardware, specifically in terms of the way secure element is connected to the NFC controller. It is independent of Android; as such it can not be subverted by malware, even when running with full privileges of the operating system.

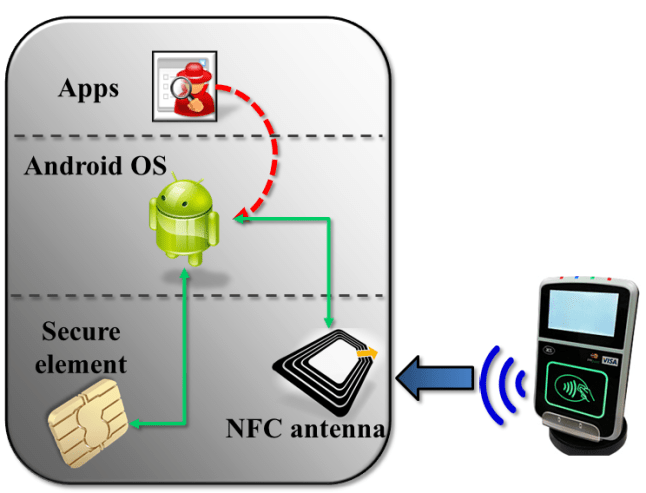

A naive picture

The seeming inevitability of relay attacks comes from a reasonable (but ultimately incorrect) picture of how the hardware is connected. Here is a naïve depiction of one reasonable architecture:

In this picture, secure element and NFC antenna are completely decoupled, independent pieces of hardware. The secure element is connected directly to the application processor, or in other words the Android operating system. When NFC transactions are performed, bits travel over the air, arrive at the NFC antenna, which dutifully routes them to the operating system in much the same way Bluetooth or 802.11 wireless interface would. (Granted there is more than an analog antenna required; there must be some circuitry to convert raw signals into meaningful data such as NFC tags being discovered.) The operating system in turn relays the commands to the SE and response is routed back in the opposite direction.

If that model was accurate, remote relay attacks would be inevitable. Since the secure element does not operate autonomously, it can only respond to commands, it can not actively go out and inspect its environment. (In fact SE is not even powered on most of the time.) Malware with sufficient privileges could “inject” traffic into the NFC stack– indicated by the red arrows above– that looks indistinguishable from traffic arriving over NFC. For that matter malware could also directly interface with SE by communicating with the device node directly. SE has no idea what is going on at the application level. It can not distinguish between remotely relayed commands versus legitimate NFC traffic originating from a nearby point-of-sale terminal.

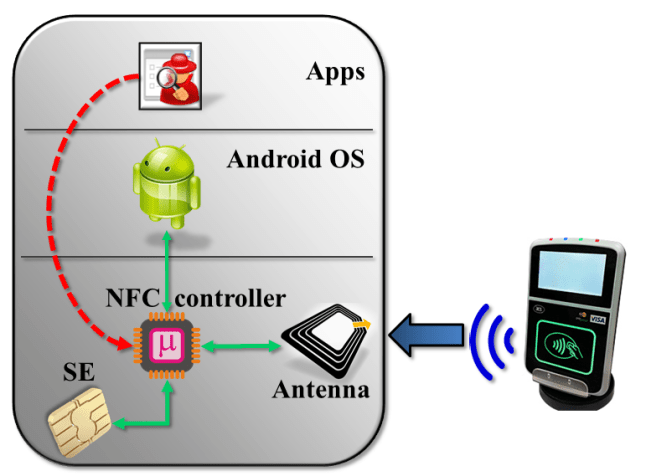

Android SE/NFC architecture

This is how the hardware is connected in reality:

The main difference is that secure element, NFC antenna and Android are not connected to each other directly; the NFC controller sits at the junction of these systems. Depending on NFC mode, that controller is responsible for routing data in different directions:

- In reader/writer and P2P modes, data flows to/from the NFC antenna to Android. SE is not involved. This is invoked for scanning tags and exchanging contacts using Android Beam.

- In wired-access mode, SE is powered on and Android communicates with SE over its wired (aka “contact”) interface. For instance when the user is entering their PIN to unlock Google Wallet, this channel is active for sending PIN down to the payment applet.

- In card-emulation mode, SE is also powered on and traffic from NFC antenna is delivered straight to the secure element, bypassing the host operating system. This is the active path when the phone is tapped against an NFC reader to complete a payment.

NFC controller and security guarantees

The last property already represents one important difference from the naïve picture. Bits are not traversing the host operating system. They go straight from NFC controller to the secure element. This provides some confidentiality, since responses from SE can not be observed by Android. But by itself it would not have been enough, unless SE can distinguish between #2 and #3.

That is where the NFC controller comes in. Additional information is communicated to the secure element about which interface commands originated from. This is not part of the command payload– otherwise it could have been forged. Instead it is metadata, made available to applications running on the SE to allow them to alter their behavior accordingly. For example Javacard exposes an API to query incoming command and distinguish between contact and contactless interfaces.** An attacker with root privileges can interface with NFC controller directly by accessing the raw device, but not the embedded secure element– this is the red arrow again. Traffic to the SE is gated by the controller, and all data coming from the host-side (whether legitimate Android NFC stack or malware attempting to relay traffic) will be tagged correctly as contact interface.

One good question is how the NFC controller itself decides to report the incoming interface. After all if this were specified by Android, it could be subverted. The answer is that logic is part of the controller firmware. Android can instruct the controller to switch into a given state such as card-emulation or wired-access mode at any time. But once in that state, all commands relayed to the secure element will be correctly tagged with the corresponding interface.

What about software attacks against the controller itself? Firmware can be updated in the field and new versions are often distributed as part of the Android image, to update hardware on initial OS boot. This would normally create another attack vector: flash the chip with corrupted firmware, designed to confuse SE about true origin of commands. But in the case of the NFC controller, new firmware versions must be digitally signed by the publisher. That signature is verified by the controller before accepting an update.

Remote-relay attacks and SE applications

Interface detection then is the fundamental mitigation against remote-relay attacks. Code executing in the secure element can differentiate between traffic from:

- Applications running on the phone– because they will be accessing the SE over contact interface

- External NFC readers such as contactless smart-card readers and point-of-sale terminals

It is up to the application to implement additional security checks based on interface. This is not always straightforward. Protocols such as Mastercard Mobile PayPass call for an application that supports some functionality over both contact and contactless interfaces. For example PIN entry and displaying information about recent transactions is done via host, while actual payments are conducted over NFC. Such an applet can not categorically reject all commands coming from contact interface. A fine-grained policy is required that takes into account internal state machine, requested command and current interface. (In fairness, EMV protocols are not unique in this regard. For example US government PIV standard for identification cards also has very specific mandates on what functionality is available over which interface.)

Weakness of host-card emulation

Returning to the comparison motivating this series–security of host card emulation vs embedded secure element— we find another significant advantage for hardware secure. Without an SE, the naïve picture does become an accurate depiction of the state of affairs. and defense against remote-relay attacks is weak. Ordinary apps can not fabricate traffic that looks like it is originating from an NFC reader. But malware that attains root privileges can pull it off, since it will be running with same privileges as the authentic Android NFC stack responsible for dispatching HCE commands to user-mode applications. By contrast, applications implemented on a hardware secure element can be secure against relay attacks even when the remote attacker is executing code as root. That is a very strong guarantee HCE can not provide.

It is also worth pointing out that this property is unique to NFC. If the payment protocol was implemented over Bluetooth or 802.11, interface detection can no longer help. In the current hardware architecture, traffic for these alternative wireless protocols must be routed through Android. This is another reason why moving the payment protocol to an execution environment in TrustZone does not produce the same security guarantee, aside from the much weaker tamper-resistance compared to actual SE. Short of a significant architectural change to move control over NFC hardware to the TrustZone kernel itself (as opposed to plain Android kernel, where NFC device driver resides today) interface detection will not be reliable.

CP

** In principle both can be active simultaneously which is why the API exists at command level. For both the NXP and Oberthur secure elements in Android, that situation can not arise. Only one interface can be used, and switching resets the SE which simplifies life for application development. All decisions about interfaces can be made at SELECT time, with the guarantee that it will not change for that session.

You must be logged in to post a comment.