Imagine you were expecting to documents from a business associate. Being reasonably concerned with op-sec, they want to encrypt the information en route. Being old fashioned, they also opt for snail-mailing an actual physical drive in the mail instead of using PGP or S/MIME to deliver an electronic copy. Is it safe to connect that USB drive that came out of the envelope? If this is bringing back memories of BadUSB, let’s take the exercise one step further: suppose this drive uses hardware-encryption and requires installing custom applications before users can access the encrypted side. But conveniently there is a small unencrypted partition containing those applications ready to install. Do you feel lucky today?

This is not hypothetical- it is how typical encrypted USB drives work.

Lost/stolen USB drives have been implicated in data breaches and encryption-at-rest is a solid mitigation against such threats. But this well-meaning attempt to improve security against one class of risks ends up reducing operational security overall against a different one: users are trained to install random applications from a USB drive that shows up in their mailbox. (It’s not a stretch to extend that bad habit to drives found anywhere, based on recent research.) Meanwhile the vendors are not helping their own case with a broken software distribution model and unsigned applications. Here is a more detailed peek at the Kingston DataTraveler Vault.

On connecting the drive, it will appear as a CD-ROM. This is not unusual; USB devices can encapsulate multiple interfaces as a single composite device. In this case the encrypted contents are not visible yet because the host PC does not have the requisite software. Looking into the contents of that emulated “CD” we find different solutions intended to cover Windows, OSX and Linux.

Windows

Considering this is an enterprise product and most enterprises are still Windows shops, one would expect the most streamlined experience here. Indeed- Windows itself recognizes the presence of an installer as soon as the drive is connected and asks about what to do. (Actually asking for user input is a major improvement over past Windows versions cursed with the overzealous autorun feature, which happily executed random binaries from any connected removable drive.)

If we decline this offer and decide to take a closer look at the installer, we can see that it has been digitally signed by the manufacturer using Authenticode, a de facto Windows standard for verifying the origin of binaries:

Looking at the digital signature of the installer in Explorer

Using the signtool utility:

Using signtool to examine Authenticode signature details

The signature includes a trusted timestamp hinting at the age of the binary. (Note the certificate is expired but the signature is still valid. This is possible only because the third-party timestamp provides evidence that the signature was originally produced at a point in time while the certificate was still valid.)

This particular signature uses the deprecated SHA1 hash algorithm, but we will give Kingston a pass on that. The urgency of migrating to better options such as SHA256 did not become apparent until long after this software had shipped. Authenticode features also include checking for certificate revocation, so we can be reasonably confident that Kingston is still in control of the private-key used to sign their binaries and they did not experience a Stuxnet moment. (Alternative view: if they have been 0wned, they are not aware of it and have not asked Verisign to revoke their certificate.)

Overall there is reasonable evidence suggesting that this application is indeed the legitimate one published by Kingston, although it may be slightly outdated given timestamps.

OSX

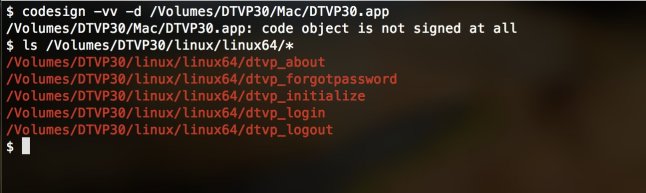

OSX applications can be signed and the codesign utility can be used to verify those signatures. Did Kingston take advantage of it? No:

What- me worry about code signing?

Not that it matters; a support page suggests that installing that application would have been a lost cause anyway:

The changes Apple made in MacOS 10.11 disabled the functionality of our secure USB drives. It will cause the error ‘Unable to start the DTXX application…’ or ‘ERR_COULD_NOT_START’ when you attempt to log into the drive. We recommend that you update your Kingston secure USB drive by downloading and installing one of the updates provided in links below.

(As an aside, it is invariably Apple’s fault when OS updates break existing applications.)

Luckily it is much easier to verify the integrity of this latest version- the download link uses SSL (although not the support page linking to the download, allowing for MITM attacks to substitute a different one.) More importantly Kingston got around to signing this one:

Linux

It is a rare surprise when any vendor attempts to get an enterprise scenario working on Linux. At this point, asking for some proof of the authenticity of binaries might be too much and the screenshot above confirms that.

In fairness Linux does not have its own native standard for signing binaries. There are some exceptions- boot loaders are signed with Authenticode thanks to UEFI requirements and some systems such as Fedora also require kernel-modules to be signed when secure-boot is used. There are also higher-level application frameworks such as Java and Docker with their own primitive code-signing schemes. But state-of-the-art code authentication in open source is PGP signatures. Typically there is a file containing hashes of files, which is cleartext signed using one of the project developers’ keys. (As for establishing trust in that key? Typically it is published on key servers and also available for download over SSL on the project pages- thus paradoxically relying on hierarchical certificate-authority model of SSL to bootstrap trust in the distribute PGP web-of-trust.) Luckily Kingston did not bother with any of that; Linux directory just contains a handful of ELF binaries without the slightest hint of verifying their integrity.

On balance

Where does that leave this approach to distributing files?

- Users on recent versions of Windows have a fighting chance to verify that they are running a signed binary (Even that small victory comes with a long list of caveats: “signed” is not a synonym for “trustworthy.” There are dangerous applications which are properly signed, including remote-access tools.)

- Users on OSX have to go out of their way to download the application from less dubious sources, by hunting around for it on the vendor website

- Linux users should abandon hope and follow standard operating procedure: launch a disposable, temporary virtual machine to run dubious binaries and hope they did not include a VM-escape exploit.

Even considering 100% Windows environments, there is collateral damage: training users that it is perfectly reasonable to run random binaries that arrive on a USB drive. In the absence of additional controls such as group policy, users are one click away from bypassing the unsigned binary warning to execute something truly dangerous. (In fact given that Windows has sophisticated plug-and-play framework with capability to download drivers from Windows Update on demand, it is puzzling that any users action to install an application is required.)

Bottom line: encrypting data on removable drives is a good idea. But there are better ways of doing that without setting bad opsec examples, such as encouraging users to install random applications of dubious provenance.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.