[Full disclosure: this blogger was formerly CSO for a cryptocurrency exchange.]

Imagine a country where confidence in the banking system has reached a nadir among the citizenry: no regulatory oversight, no lending standards, no requirement for public audits and no FDIC insurance to serve as backstop in the event of bank failure. Instead consumers a coalition of consumers decide to take matters into their own hands with a grassroots campaign to verify the solvency of banks. How? By orchestrating a bank-run. Everyone is instructed to take out all of their money out of banks on the same day and deposit them back at a later time after observing to their satisfaction that all withdrawals have been processed successfully.

This is not an entirely far-fetched analogy for what happened in the cryptocurrency space earlier this month with the Proof of Keys event. There are of course key differences, no pun intended. Traditional banks operate a fractional reserve by design. It is no secret they would experience a liquidity problem if all customers showed up to demand 100% of their deposits at the same time, as epitomized in the bank-run scene from It’s a Wonderful Life. But cryptocurrency businesses operate under a different expectation, namely that they retain full custody of customer deposits at all times. No lending, no proprietary trading, not even parking those funds at an interest-bearing account offered by another financial institution lest it create counter-party risk. So on the face of it, there is some value to this withdraw & redeposit ritual: a custodian successfully satisfying every withdrawal was provably in possession of those customer funds.

But the reasoning is flawed for several reasons.

First, participation is voluntary. Even with viral propagation on social media and decent coverage in press outlets dedicated to cryptocurrency, only a small fraction of users representing an even smaller fraction of total funds will participate. (It is easier for retail investors to participate, compared to an institution such as hedge-fund. The latter typically have more stringent requirements around alternative places to keep funds. An off-the-shelf hardware wallet is an adequate solution for storing personal funds; it is a far cry from enterprise-grade storage with redundancy and multiple users for an institution.) While exact numbers are not available, mining fees and memory pool pressure statistics can be used as a gauge of participation. Assuming only 10% of funds were withdrawn from a given exchange, the campaign has only proven that at least 10% of funds are there.

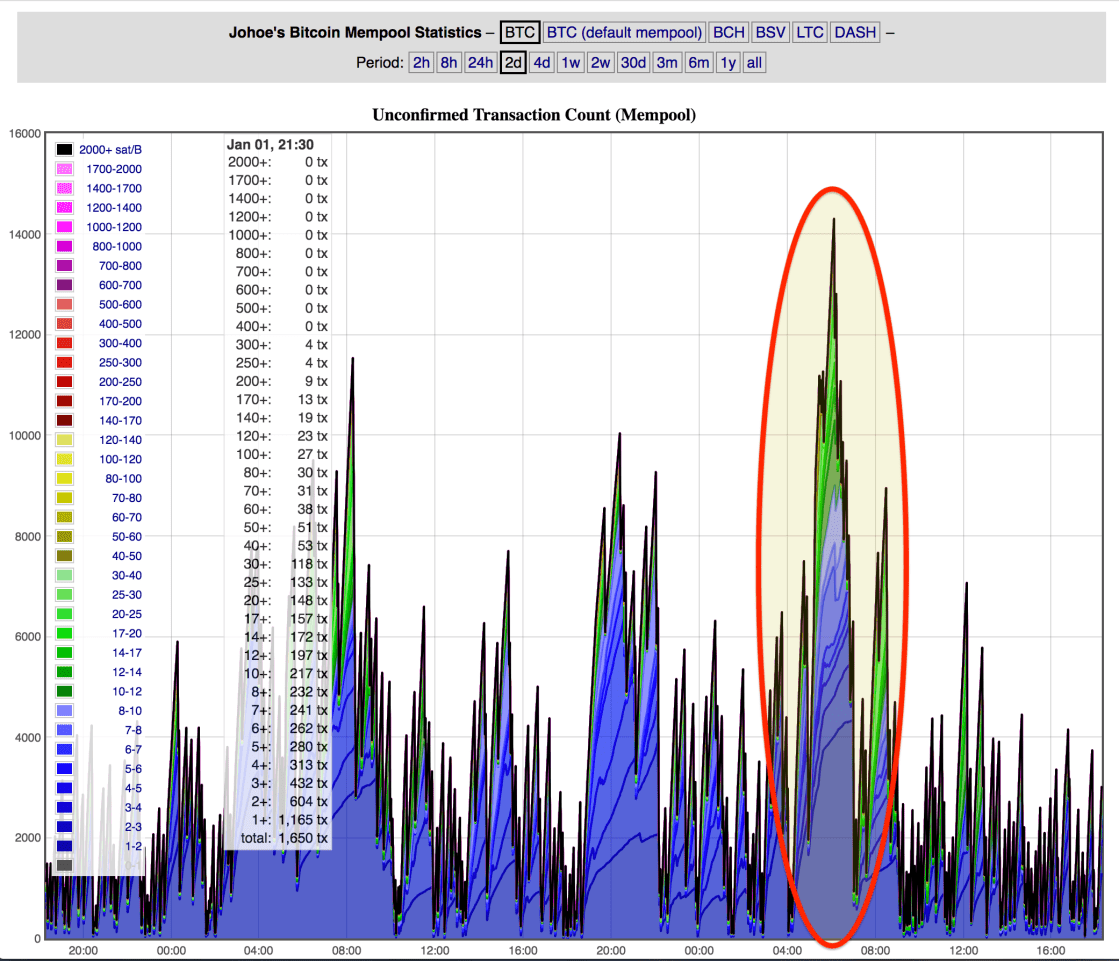

Zooming on mempool state on January 3rd shows a temporary spike, coinciding with morning hours in PST.

Looking at 30-day view paints a different picture. There is nothing remarkable about the transaction volume or fees on January 3rd.

Second, pre-announcing a bank-run ahead of time somewhat defeats the point. It’s not a pop-quiz if the teacher announces that there will be a pop-quiz next Friday. Given enough advance warning, even custodians who were actively investing their deposits can convert all of the capital back to the expected currency.

Finally there is a more subtle reason why this stress-test for custodians fails: it is first and foremost a test of liquidity instead of solvency. In other words, it is subject to false negatives where even a cryptocurrency custodians with 100% of funds on deposit could fail to produce every last satoshi on demand, for a very good reason. Sound risk management for cryptocurrency dictates storing the majority of funds offline, in cold storage. By definition these systems are disconnected from the Internet and require manual steps—such as travel to an offsite location—to effect a withdrawal. Only a small fraction of funds are kept “online” in hot wallets, where they are instantly accessible for satisfying withdrawal requests.

This model is similar to how traditional banks manage cash. Even within a single branch, only a fraction of the cash present at that branch is loaded into the ATM. The remainder would be kept in an interior vault within the branch. Banknotes stuffed into the ATM are available 24/7 for customers to withdraw but also come with a downside: they are subject to heightened risk of theft. Blowing up an ATM or towing it away is easier than breaking into a steel vault. By keeping only sufficient money in the ATM to satisfy expected withdrawal volume, the bank manages its exposure while providing high degree of assurance that customers will have access to their funds. As long as projected liquidity requirements are not too far off the actual observed demand from customers— in other words, barring unexpected events that result in everyone rushing to the ATM at once—this is a good trade-off between security and liquidity.

Cryptocurrency custodians employ a similar strategy for managing the exposure of hot-wallets. If deposits exceeds withdrawals and there is a net influx of funds, the wallet may start running too “hot.” Excess risk is trimmed by sending funds to an offline wallet. Since the transfer is initiated from an online wallet accessible over a network, this step is easy. On the other hand, if withdrawals outpace deposits and there is a net outflow, the system risks running into a liquidity problem and must be replenished by moving funds back from an offline wallet. This step is more time consuming. By design, access to offline wallets is available from the same system operating the hot wallet; otherwise they would be subject to same risks as the lower-lower-assurance system.

Returning to the conceptual problem with the DIY proof-of-solvency, if enough customers actually participate in a coordinated effort to withdraw their funds at the same time, hot-wallets will bottom out and cease to provide liquidity until they are replenished from offline wallets. (Granted, knowing when the stress-test will occur creates additional options to prep. For example the custodian can deliberately bias the wallet distribution to maintain higher-than-usual fraction of funds online.) That means events such as January 3rd are not so much a proof of solvency as they are a proof of available hot-wallet liquidity or perhaps time-trial of how fast the custodian can access offline storage systems. The paradoxical part is that in any system with online/offline separation managed according to risk criteria, some delay in processing withdrawals would be fully expected. If anything, it is a bad sign if the custodian can instantly produce 100% of all funds on short notice. It means they are likely keeping 100% of cryptocurrency online in a hot-wallet, where they are most susceptible to theft. Ask Bitfinex how that turned out in 2016.

To be clear: this is not to trivialize security concerns with storage of cryptocurrency. Given that internal workings of exchanges and custodians remain opaque to most customers, it is completely reasonable to demand periodic assurance that funds deposited with are still accounted for. Considering that proof-of-keys suffers from conceptual flaws and indeed accomplished very little this time around (judging by observed withdrawal volume) the question becomes: what is an effective way for custodians to verify that a custodian is still in possession of their cryptocurrency deposits? A future blog post will look at some alternatives.

CP