[continued from part II]

The final post in this series pushes the threat model into tinfoil-hat territory: we posit Amazon going rogue or being compelled to recover private, encrypted data associated with users of the AWS Storage Gateway service.

Data corruption: attacks against integrity

An obvious avenue for Amazon to attack customers is by modifying gateway software to return corrupted data. As noted earlier, full-disk encryption schemes operate under a strict constraint that 1 block of plaintext must encrypt to exactly 1 block of ciphertext. No expansion of data is allowed. This rules out use of integrity checks to detect corruption of ciphertext. Every block returned by the gateway will decrypt to something; that could be the original data stored by the customer— or not. At most FDE can guarantee is that without the encryption key, Amazon can not return a ciphertext crafted to yield some plaintext of their choosing.

What can be achieved in this limited attacker model is highly dependent on content type. Scrambling a few pixels in a picture or ruining the beat for a few seconds in a song is unlikely to ruin anyone’s day. On the other hand, randomly changing figures in a spreadsheet used for financial reporting may have downstream implications— although such files have additional structure that will likely break when a 512-byte sector is perturbed. If remote storage is used for storing executable files, worst-case scenario is arbitrary code execution. Yet achieving that requires a level of control over data corruption that is unlikely with FDE. Replacing a block of code with random x86 instructions will result in a crash with high probability.

More interesting potential targets are files holding configuration data which influence how software behaves. Again it is possible to come up with contrived examples where even a random change could alter system security level. For example consider a binary format where one field is assumed to hold a boolean flag determining whether a dangerous feature such as macros or debugging are enabled. A value of zero indicates off, any other value stands for on. With very high probability any change to ciphertext will flip this flag from “off” to “on,” enabling a potentially exploitable feature. (Granted exploiting that is still non-trivial: attacker would have to know the exact location of the file on disk along with offset of that critical field inside the file. Recall that the concept of a “file” does not exist at iSCSI layer: cloud storage provider only observes requests for reading and writing blocks containing encrypted data. Metadata including file names is not visible, although some properties such as existence of a file spanning particular blocks could be inferred from access patterns.)

Lateral movement: attacks against customer systems

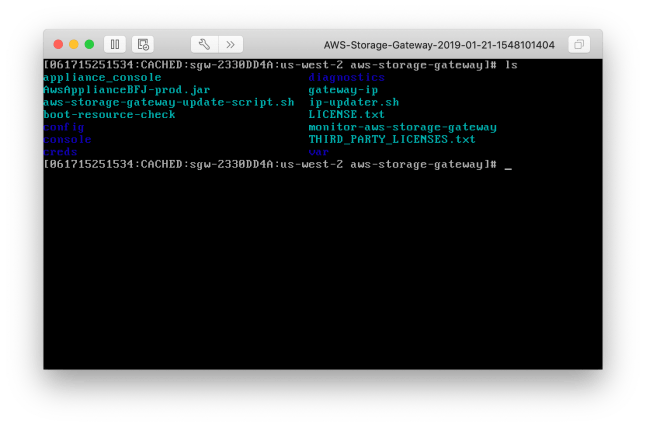

A more promising attack strategy is Amazon pushing out a malicious update to the gateway VM that seeks to escalate privileges outside the gateway itself, taking over other systems in the customer environment. Objective: discover the secret key used for full-disk encryption by compromising the system that applies FDE over the raw block device. That attack vector exists even if a TPM or smart-card is used for key management; at the end of the day there is a symmetric key released to the FDE implementation, regardless of whether that secret was originally wrapped by a password typed by the user or cryptographic hardware.

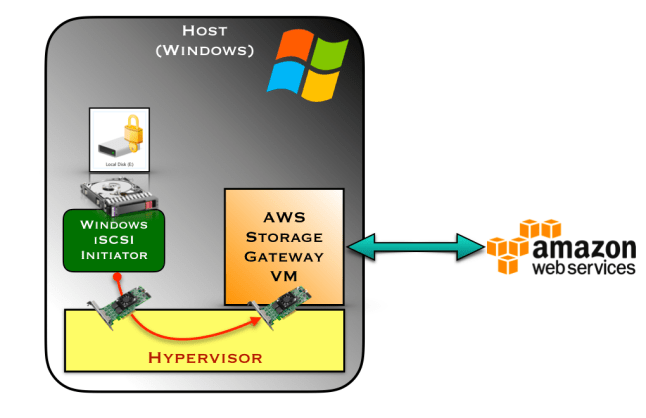

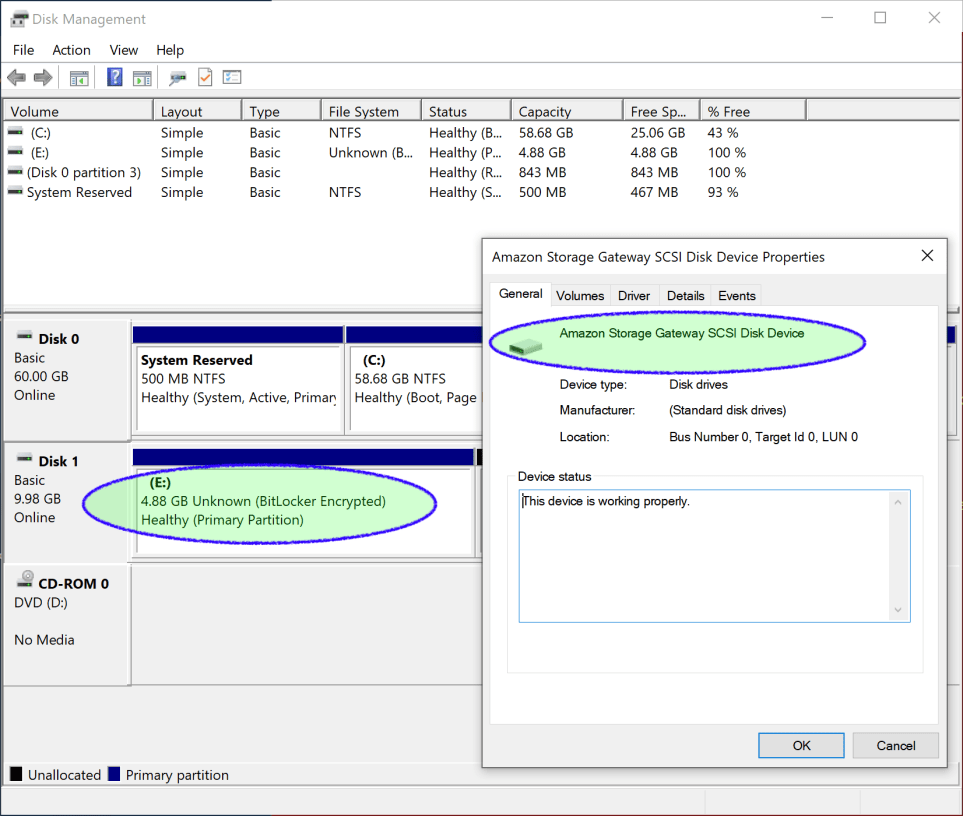

Considering the gateway VM as a malicious system seeking lateral movement, we find that it has few resource available. These VMs require very little integration with the surrounding environment: they do not need to be joined to an Active Directory, they do not SSH into any other customer system or access resources from a file share. In fact it can be isolated from the environment with the exception of inbound ports for iSCSI ports and external communication to AWS. Focusing on inbound connections, only a handful of other customers systems interact with the VM and specifically over iSCSI interface. It would take a remote-code execution bug in the iSCSI initiator to allow lateral movement, by having the iSCSI target return iSCSI responses to the vulnerable initiator.

A more likely target is the physical machine hosting the gateway VM. While not common, vulnerabilities are periodically discovered in hypervisors that would permit guest VMs to “break out” and take over the host. (It is also a safe assumption that Amazon could conduct reconnaissance to identify which hypervisor their customer is running and choose an appropriate exploit, not wasting a VMware 0-day on a customer running Hyper-V) This risk is much higher for the simple deployment model, where gateway VM is colocated with the second machine (virtual or physical) that implements full-disk encryption. In that scenario, a full VM escape may not even be required: micro-architectural side channel attacks could permit AWS to recover an AES key or plaintext lying around in memory from computations performed by the colocated FDE implementation. Hosting the VM on dedicated hardware physically separated from the machine that implements full disk encryption mitigates this risk.

One deterring factor against these tactics— in addition to their long odds of success—is they would be very noisy. Deploying a malicious update or serving a tampered iSCSI volume to the gateway VM leaves trails on local disk. Amazon can not rule out the possibility that the customer is making periodic backups of their VM or copying remote files to another local device outside Amazon control. That would result in the customer having a permanent record of an attempted attack for future forensics.

Economics: cost of privacy

To summarize: AWS Storage Gateway provides a pragmatic model for using cloud-storage services for private storage— as a glorified drive storing encrypted bits, with no way for the service provider to decrypt those bits. This is in marked contrast from the standard model of cloud storage where providers have full visibility into customer data, and either promise to not to peek or only peek for specific business objectives such as advertising. As with all DIY projects, there are tradeoffs to achieving that level of privacy. From a cost perspective, there is no charge for using a gateway appliance per se. instead AWS charges standard S3 storage rates for the space used, along with standard EC2 rates for outbound data transfer from AWS cloud to the gateway. Inbound bandwidth from the gateway appliance to the cloud for backing up modified data is free, but there is a charge per-GB for new data written to the volume. To pick one data point, keeping 10TB of private storage of which 10% gets modified every month would cost about two to three times more compared to a standard consumer offering such as Google Drive, depending on AWS region since Amazon prices vary geographically. That does not include the cost for hardware and operational expenses for running the gateway appliance itself. That incremental expense may vary from nearly zero— when adding one more VM to an existing load that already runs 24/7— to significant if new hardware must be acquired for hosting the gateway appliance.

Unlike other DIY projects such as hosting your own VPN service where AWS is less cost-effective than alternative hosting services, in this scenario AWS fares much better competitively. Cost of self-hosted VPN is largely dominated by bandwidth, where the AWS fee structure for charging by GB quickly loses against flat pricing models. But when it comes to using the cloud as a glorified disk drive storing bits, the specialized nature of AWS Storage Gateway has an edge. Replicating the same solution by attaching large SSD storage to a leased virtual server would neither cost effective or achieve a comparable level of redundancy as leveraging AWS.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.