[This is an expanded version of what started out as a Twitter thread]

Fighting spam and failing our customers

When Twitter announced its tweet-by-voice feature, they were probably not expecting the backlash from users with disabilities pointing out that the functionality would be unusable in its present state. It is not the first time technology companies forget about accessibility in the rush to ship features out the door. This is one such story from this blogger’s time at MSFT.

Outbound spam problem

In the early 2000s, MSFT Passport was the identity service for all customer-facing online services the company provided: Hotmail, MSN properties, Xbox Live and even developer-facing services including MSDN. (Later renamed Windows Live and now known simply as MSFT Accounts, not to be confused with a completely unrelated Windows authentication feature named “Passport” that retired in 2016.) This put the Passport team— my team— squarely in the midst of a raging battle against outbound spam. Anyone hosting email has to contend with inbound spam and keeping that constant stream out of their customers inbox. But service providers who give away free email accounts also have to worry about the opposite problem: crooks registering for thousands of such free accounts and enlisting the massive resources available to a large-scale provider like Hotmail to push out their fraudulent messages. Since Passport handled all aspects of identity including account registration, it became the first bulwark against keeping spammers out.

While most problems in economics have to do with pricing, the problem of spam originates with complete absence of cost. If customers had to pay for every piece of email they sent or even charged a monthly subscription fee for the privilege of having a Hotmail account, no spammer would find it profitable to use Hotmail accounts for their campaign. But the Orginal Sin of the web is an unshakeable conviction that every service must be “free,” at least on the surface. To the extent that companies are to make money, this doctrine goes, services shall be monetized indirectly— subsidized by some other profitable line of business such as hardware coupled to the service or increasingly, data-mining customer information for increasingly targeted and intrusive advertising, which begat our present form of Surveillance Capitalism. To the extent charges could be levied, they had to be indirect.

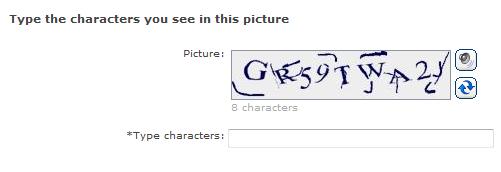

Enter CAPTCHAs. This unwieldy acronym stands for “Completely Automated Public Turing-test to tell Computers and Humans Apart.” In the early 2000s the terminology had not been standardized. At MSFT we used the simpler acronym HIP for Human Interaction Proof. The basic idea is having a puzzle that is easy for humans but difficult for computers to solve. The most common example is recognizing distorted letters inside an image. Solving that puzzle becomes the new toll booth for access to an otherwise “free” service. So there is a price introduced but it is charged in the currency of human cognitive workload. Of course spammers are human too: they can sit down and solve these puzzles all day long— or pay other people in developing countries to do so, as researchers eventually discovered happening in the wild. But they can not scale it the same way any longer: before they could register accounts about as fast as their script could post data to Passport servers. Now each one of those registration attempts must be accompanied by proof that someone somewhere devoted a few seconds worth of attention to solve a puzzle.

Designing CAPTCHAs

So what does an ideal CAPTCHA look like? Recall that the ideal puzzle is easy for humans but difficult for computers. This is a moving target: while our cognitive capacity changes very slowly over generations of evolution, the field of artificial intelligence moves much faster to close the gap.

Philosophically, there is no small measure of irony in computers scientists devising such puzzles. The very idea of a CAPTCHA contradicts common interpretations of the Church-Turing thesis, one of the founding principles of computer science. Named after Alan Turing and his advisor Alanzo Church, the thesis states that the notion of a Turing machine— an idealized theoretical model of computers we can construct today, but with infinite memory— captures the notion of computability. According to this thesis, any computational problem that is amenable to “solution” by mechanical procedures can be solved by a Turing machine. Its original formulated was squarely in the realm of mathematics but it did not take long for inevitable connection to physics and philosophy of mind to emerge. One interpretation holds that since the human mind can solve certain complex problems—recognizing faces or understanding language— it ought to be possible to implement the same steps for solving that problem on a computer. In this view popular among AI researchers, there can not be a computational problem that is magically solvable by humans and forever out of reach of algorithms. That makes computer science research on CAPTCHAs somewhat akin to engineers designing perpetual motion machines.

Of course few researchers actually believe such problems fundamentally exist. Instead we are simply exploiting a temporary gap between human and AI capabilities. It is a given that AI will continue to improve and encroach into that space of problems temporarily labelled “only solvable by humans.” In other words, we are operating on borrowed time. It is not surprising that many CAPTCHA designs originated with AI researchers: defense and offense feed each other. Less known is that Microsoft Research was at the forefront of this field in the early 2000s. In addition to designing the Passport CAPTCHA, MSR groups broke CAPTCHAs deployed by Ticketmaster, Yahoo and Google, publishing a paper on the subject. (This blogger reached out to affected companies ahead of time with vulnerability notification and make sure there were no objections to publication.) For CAPTCHAs based on recognizing letters, we knew that simple distortion or playing tricks with colors would not be effective. Neural networks are too good at recognizing stand-alone letters. Instead the key is preventing segmentation: make it difficult for OCR to break up the image into distinct letters, by introducing artificial strokes that connect the archipelago of letters into one uninterrupted web of pixels.

Some trial-and-error was necessary to find the right balance. The first version proved way too easy. In fact it turned out that around the same time Microsoft Office introduced an OCR capability for scanning images into a Word document and that feature alone could partially decode some of the CAPTCHAs. Facepalm moment: random feature in one MSFT product 0wns the security feature of another MSFT product. We can only hope this at least spurred the sales— or more likely pirating— of Office 2003 among enterprising spammers. After some tweaks to the difficulty parameters, image CAPTCHAs settled on a healthy middle-ground, stemming the tide of bogus accounts created by spammers without stopping honest customers from signing up.

There was one major problem remaining however: accessibility. Visual CAPTCHAs work fine for users who could see the images. What about customers with visual disabilities?

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.