The Trusted Platform Module (TPM) plays a critical role in measured boot: verifying that the state of a machine after booting into the operating system. This is accomplished by a chain of trust rooted in the firmware, with each link in the chain recording measurements of the next link in the TPM before passing control to its successor. For example, the firmware measures option ROMs before executing each one, then the master-boot record (for legacy BIOS) or GPT configuration (for EFI) before handing control over to the initial loader such as the shim for Linux, which in turn measures the OS boot-loader grub. These measurements are recorded in a series of platform-configuration registers or PCRs of the TPM. These registers have the unusual property that consecutive measurements can only be accumulated; they can not be overwritten or cleared until a reboot. It is not possible for a malicious component coming later in the boot chain to “undo” a previous measurement or replace it by a bogus value. In TPM terminology one speaks of extending a PCR instead of writing to the PCR, since the result is a function of both existing value present in the PCR— the history of all previous measurements accumulated so far— and current value being recorded.

At the end of the boot process, we are left with a series of measurements across different PCRs. The question remains: what good are these measurements?

TPM specifications suggest a few ideas:

- Remote attestation. Prove to a third-party that we booted our system in this state. TPMs have a notion of “quoting”— signing a statement about the current state of the PCRs, using an attestation key that is bound to that TPM. The statement also incorporates a challenge chosen by our remote peer, to prove freshness of the quote. (Otherwise we could have obtained the quote last week and then booted a different image today.) As side-note: remote attestation was one of the most controversial features of the TPM specification, because it allows remote peers to discriminate based on software users are running.

- Local binding of keys. TPM specification has an extensive policy language around controlling when keys generated on a TPM can be used. In the basic case, it is possible to generate an RSA key that can only be used when a password is supplied. But more interestingly, key usage can be made conditional on the value of a persistent counter, the password associated with a different TPM object (this indirection allows changing password all at once on multiple keys) or specific values of PCRs. Policies can also be combined using logical conjunctions and disjunctions.

PCR policies are the most promising feature for our purposes. hey allow binding a cryptographic key to a specific state of the system. Unless the system is booted into this exact state— including the entire chain from firmware to kernel, depending on what is measured— that key is not usable. This is how disk-encryption schemes such as Bitlocker and equivalent DIY-implementations built on LUKS work: the TPM key encrypting the disk is bound to some set of PCRs. More precisely, the master key that is used to encrypt the disk is itself “wrapped” using a TPM key that is only accessible when PCRs are correct. Upshot of this design is that unless the boot process results in the same exact PCR measurements, disk contents can not be decrypted. (Strictly speaking, Bitlocker uses another way to achieve that binding. TPM also allows defining persistent storage areas called “NVRAM indices.” In the same way usage policies can be set on PCR, NVRAM indices can be associated with an access policy such that their contents are only readable if PCRs are in a given state.)

To see what threats are mitigated by this approach, imagine a hypothetical Bitlocker-like scheme where PCR bindings are not used and a TPM key exists that can decrypt the boot volume on a laptop without any policy restrictions. If that laptop is stolen and an adversary now has physical access to the machine, she can simply swap out the boot volume with a completely different physical disk that contains a Linux image. Since that image is fully controlled by the attacker, she can login and run arbitrary code after boot. Of course that random image does not contain any data from the original victim disk, so there is nothing of value to be found immediately. But since the TPM is accessible from this second OS, attacker can execute a series of commands to ask the TPM to decrypt the wrapped-key from the original volume. Absent PCR bindings, the TPM has no way to distinguish between the random Linux image that booted and the “correct” Windows image associated with that key.

The problem with PCR bindings

This security against unauthorized changes to the system comes at the cost of fragility: any change to PCR values will render TPM objects unusable, including those that are “honest.” Firmware itself is typically measured into PCR0 and if a TPM key is bound to that PCR, it will stop working after the upgrade. In TPM2 parlance, we would say that it is no longer possible to satisfy the authorization policy associated with the object. (In fact, since firmware upgrades are often irreversible to avoid downgrading to vulnerable versions, that policy is likely never satisfiable again.) The extent of fragility depends on selected PCRs and frequency of expected changes. Firmware upgrades are infrequent, they are increasingly integrated with OS software update mechanism such as fwupd on Linux. On the other hand, Linux Integrity Measurement Architecture or “IMA” feature measures key operating system binaries into PCR10. That measurement can change frequently with kernel and boot-loader upgrades. In fact since IMA is configurable in what gets measured, it is possible to configure it to measure more components and register even minor OS configuration tweaks. There is intrinsic tension between security and flexibility here: the more OS components are measured, fewer opportunities left for an attacker to backdoor the system unnoticed. But it also means fewer opportunities to modify that system since any change to a measured component will brick keys bound to those measurement.

There are some work-arounds for dealing with this fragility. In some scenarios, one can deal with an unusable TPM key by using an out-of-band backup. For example, LUKS disk encryption supports multiple keys. In case the TPM key is unavailable, the user can still decrypt using a recovery key. Bitlocker also supports multiple keys but MSFT takes a more cautious approach, recommending that full-disk encryption is suspended prior to firmware updates. That strategy does not work when the TPM key is the only valid credential enabling a scenario. For example when an SSH or VPN key is bound to PCRs and the PCRs change, those credentials need to be reissued.

Another work-around is using wildcard policies. TPM2 policy authorizations can express very complex statements. For example wildcard policies allow an object to be used as long as an external private-key signs a challenge from the TPM. Similarly policies can be combined using logical AND and OR operators, such that a key is usable either based on correct PCR values or a wildcard policy as fallback. In this model, decryption would normally use PCR bindings but in case the PCRs have changed, some other entity would inspect the new state and authorize use of the key if those PCRs look healthy.

Surfacing PCR measurements

In this proof-of-concept, we look at solving a slightly orthogonal problem: surfacing PCR measurements to the owner for that person make a trust decision. That decision may involve providing the wildcard authorization or something more mundane, such as entering the backup passphrase to unlock their disk. More generally, PCR measurements on a system can act as a health check, concisely capturing critical state such as firmware version, secure-boot mode and boot-loader used. Users can then make a decision about whether they want to interact with this system based on these data points.

Of course simply displaying PCRs on screen will not work. A malicious system can simply report the expected healthy measurements while following a different boot sequence. Luckily TPMs already have a solution for this, called quoting. Closely related to remote attestation, a quote is a signed statement from the TPM that includes a selection of PCRs along with a challenge selected by the user. This data structure is signed using an attestation key, which in turns is related to the endorsement key that is provisioned on the TPM by its manufacturer. (The endorsement key comes with an endorsement certificate baked into the TPM to prove its provenance, but it can not be used to sign quotes directly. In an attempt to improve privacy, TCG specifications complicated life by requiring one level of indirection with attestation keys, along with an interactive challenge/response protocol to prove relationship between EK and AK.) These signed quotes can be provided to users after boot or even during early boot stages as datapoint for making trust decisions.

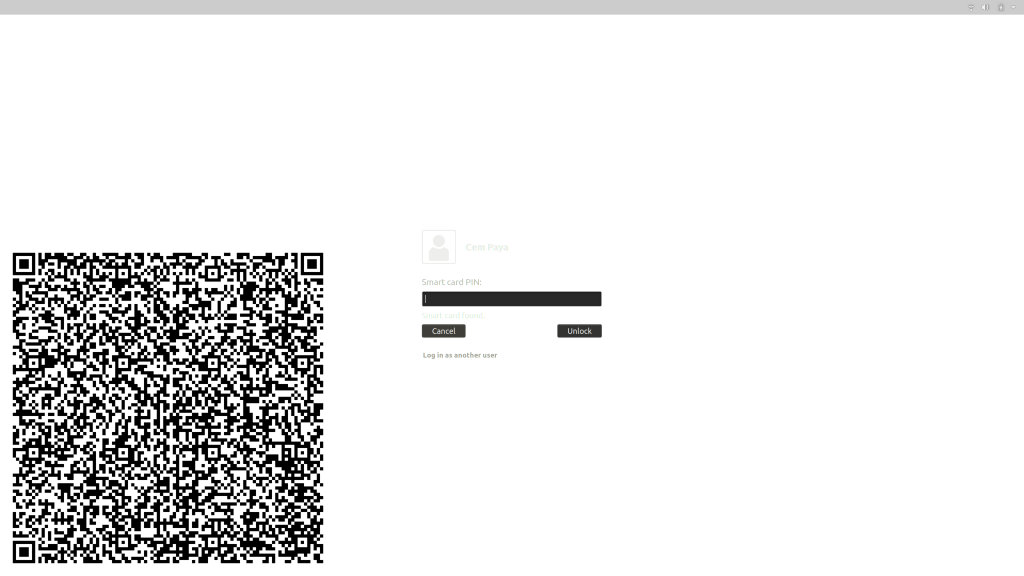

Proof-of-concept with QR codes

There are many ways to communicate TPM quotes to the owner of a machine: for example the system could display it as text on screen, write out the quote as regular file on a removable volume such as USB drive or leverage any network interface such as Ethernet, Bluetooth or NFC to communicate them. QR codes have the advantage of simplicity in only requiring a display on the quoting side and a QR scanning app on the verification side. This makes it particularly suited to interactive scenarios where the machine owner is physically present to inspect its state. (For non-interactive scenarios such as servers sitting in a datacenter, transmitting quotes over the network would be a better option.)

As a first attempt, we can draw the QR code on the login background screen. This allows the device owner to check its state after it has booted but before the owner proceeds to enter their credentials. The same flow would apply for unlocking the screen after sleep/hibernation state. First step is to point the default login image. Several tutorials describe customizing the login screen for Ubuntu by tweaking a specific stylesheet file. Alternatively there is the gdm-settings utility for a more point-and-click approach. The more elaborate part is configuring a task to redraw that image periodically. Specifically, we schedule a task to run on boot and every time the device comes out of sleep. This task will:

- Choose a suitable challenge to prove freshness. In this example, it retrieves the last block-hash from the Bitcoin blockchain. That value is updated every 10 minutes on average, can be independently confirmed by any verifier consulting the same blockchain and can not be predicted/controlled by the attacker. (For technical reasons, the block hash must be truncated down to 16 bytes, the maximum challenge size accepted by TPM2 interface.)

- Generate a TPM quote using the previously generated attestation key. For simplicity, the PoC assumes that AK has been made into a persistent TPM object to avoid having to load it into the TPM repeatedly.

- Combine the quote with additional metadata, most important one being actual PCR measurements. The quote structure includes a hash of the included PCRs but not the raw measurements themselves. Recall that our objective is to surface measurements so the owner can make an informed decision, not proving that they equal to a previously known reference value. If expected value was cast in stone and known ahead of time, one could instead use PCR policy to permanently bind some TPM key to those measurements instead, at the cost of fragility discussed earlier. (This PoC also includes the list of PCR indices involved in the measurement for easy parsing, but that is redundant as the signed quote structure already includes that.)

- Encode everything using base64 or another alphabet that most QR code applications can handle. In principle QR codes can encode binary data but not every scannerhandles this case gracefully.

- Convert that text into a PNG file containing its QR representation and write this image out on the filesystem where we previously configured Ubuntu to locate its background image.

This QR code now contains sufficient information for the device owner to make a trust decision regarding the state of the system as observed by the TPM.

Corresponding verification steps would be:

- Decode QR image

- Parse the different fields and base64 decode to binary values

- Verify the quote structure using the public half of the TPM attestation key

- Concatenate actual PCR measurements including in the QR code, hash the resulting sequence of bytes and verify that this hash is equal to the hash appearing inside the quote structure. This step is necessary to establish that the “alleged” raw PCR measurements attached to the quote are, in fact, the values going into that quote.

- Confirm that the validated PCR measurements represent a trustworthy state of the system.

Step #5 is easier said than done, since it is uncommon to find public sources of “correct” measurements published by OEMs. Most likely one would take a differential approach, comparing against previous measurements from the same system or measurements taken from other identical machines in the fleet. For example, if applying a certain OS upgrade to a laptop in known healthy state in the lab produces a set of measurements, one can conclude that observing the same PCRs on a different unit from the same manufacturer is not unexpected occurrence. On the other hand, if a device mysteriously starts reporting a new PCR2 value—associated with option ROMs from peripheral devices that are loaded by firmware during boot stage— it may warrant further investigation by the owner.

Moving earlier in the boot chain

One problem with using the lock-screen to render TPM quotes is that it is already too late for certain scenario. Encrypted LUKS partitions will already have been unlocked at that point, possibly by the user entering a passphrase or their smart-card PIN during the boot sequence. That means a compromised operating system already has full access to decrypted data by the time any QR code appears. At that point the QR code still has some value as a detection mechanism, as the TPM will not sign a bogus quote. An attacker can prevent the quote from being displayed, feign a bug or attempt to replay a previous quote containing stale challenges but these all produce detectable signals. More subtle attempts may wait until disk-encryption credentials have been collected from the owner, exfiltrate those credentials to attacker-controlled endpoint, fake a kernel panic to induce reboot back into a healthy state where the next TPM quote will be correct.

With a little more effort, the quote rendering can be moved to earlier in the boot sequence and give the device owner an opportunity to inspect system state before any disks are unlocked. The idea is to move the above logic into the initrd image which is a customizable virtual disk image that contains instructions for early boot stages after EFI firmware has already passed control to the kernel. Initrd images are customized using scripts that execute at various stages. By moving the TPM quote generation to occur around the same time as LUKS decryption, we can guarantee that information about PCR measurements are available before any trust decisions are made about the system. While the logic is similar to rendering QR quotes on the login screen, there are several implementation complexities to work around. Starting with the most obvious problem:

- Displaying images without the benefit of a full GUI framework. Frame-buffer to the rescue. It turns out that this is already a solved problem for Linux: fbi and related utilities can render JPEG or PNGs even while operating in console mode by writing directly to the frame-buffer device. (Incidentally it is also possible to take screenshots by reading from the same device; this is how the screenshot attached below was captured.)

- Sequencing, or making sure that the quote is available before the disk is unlocked. One way to guarantee this is to force quote generation to occur as integral part of LUKS unlock operation. Systemd has removed support for LUKS unlock scripts, although crypttab remains an indirect way to execute them. In principle we could write a LUKS script that invokes the quote-rendering logic first, as a blocking element. But this would create a dependency between existing unlock logic and TPM measurement verification. (Case in point: unlocking with TPM-bound secrets used to require custom logic but is now supported out of the box with systemd-cryptenroll.)

- Stepping back, we only need to make sure that quotes are available for the user to check, before they supply any secrets such as LUKS passphrase or smart-card PIN to the system. There is no point in forcing any additional user interaction, since a user may always elect to ignore the quote and proceed with boot. To that end this PoC handles quote generation asynchronously. It opens a new virtual terminal (VT) and brings it to the foreground. All necessary work for generating the QR code— including prompting the user for optional challenge— will take place in that virtual terminal. Once the user exits the image viewer by pressing escape, they are switched back to the original VT where the LUKS prompt awaits. Note there is no forcing function in this sequence: nothing stops the user from ignoring the quote generation logic and invoking the standard Ctrl+Alt+Function key combination to switch back to the original VT immediately if they choose to.

- Choosing challenges. Automatically retrieving fresh quotes from an external, verifiable source of randomness such as the bitcoin blockchain assumes network connectivity. While basic networking can be available inside initrd images and even earlier during the execution of EFI boot-loaders, it is not going to be the same stack running as the operating system itself. For example, if the device normally connects to the internet using a wifi network with the passphrase stored by the operating system, that connection will not be available until after the OS has fully booted. Even for wired connections, there can be edge-cases such as proxy configuration or 802.1X authentication that would be difficult to fully replicate inside the initrd image.

This PoC takes a different tack to work around networking requirement, by using a combination of EFI variables and prompting the user. For the sunny-day path, the EFI variable is updated using an OS task scheduled to execute at shutdown, writing the same challenge (eg most recent block-hash from Bitcoin) into firmware flash. On boot this value will be available for the initrd scripts to retrieve for quote generation. If the challenge did not update correctly eg during a kernel-panic induced reboot, the owner can opt for manually entering a random value from the keyboard.

Another minor implementation difference is getting by without a TPM resource manager. When executing in multi-user mode, TPM access is mediated by the tabrmd service, which stands for “TPM Access Broker and Resource Manager Daemon.” That service has exclusive access to the raw TPM device typically at /dev/tpm0 and all other processes seeking to interact with the TPM communicate with the resource manager over dbus. While it is possible to carry over the same model to initrd scripts, it is more efficient to simply have our TPM commands directly access the device node since they are executing as root and there is no risk of contention from other processes vying for TPM access.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.