Privacy leaks in TLS client authentication

Spot the Fed is a long-running tradition at DefCon. Attendees try to identify suspected members of law enforcement or intelligence agencies blending in with the crowd. In the unofficial breaks between scheduled content, suspects “denounced” by fellow attendees as potential Feds are invited on stage— assuming they are good sports about it, which a surprising number prove to be— and interrogated by conference staff to determine if the accusations have merit. Spot-the-Fed is entertaining precisely because it is based on crude stereotypes, on a shaky theory that the responsible adults holding button-down government jobs will stand out in a sea of young, irreverent hacking enthusiasts. While DefCon badges feature a cutting-edge mix of engineering and art, one thing they never have is identifying information about the attendee. No names, affiliation or location. (That is in stark contract to DefCon’s more button-down, corporate cousin, Blackhat Briefings which take place shortly before DefCon. BlackHat introductions often start with attendees staring at each others’ badge.)

One can imagine playing a version of Spot the Fed online: determine which visitors to a website are Feds. While there are no visuals to work with, there are plenty of other signals ranging from the visitor IP address to the specific configuration of their browser and OS environment. (EFF has a sobering demonstration on just how uniquely identifying some of these characteristics can be.) This blog post looks at a different type of signal that can be gleamed from a subset of US government employees: their possession of a PIV card.

Origin stories: HSPD 12

The story begins in 2004 during the Bush era with an obscure government edict called HSPD12: Homeland Security Presidential Directive #12:

There are wide variations in the quality and security of identification used to gain access to secure facilities where there is potential for terrorist attacks. In order to eliminate these variations, U.S. policy is to enhance security, increase Government efficiency, reduce identity fraud, and protect personal privacy by establishing a mandatory, Government-wide standard for secure and reliable forms of identification issued by the Federal Government to its employees and contractors […]

That “secure and reliable form of identification” became the basis for one of the largest PKI and smart-card deployments. Initially called CAC for “Common Access Card” and later superseded by PIV or “Personal Identity Verification,” these two programs combined for the issuance of millions of smart-cards bearing X509 digital certificates issued by a complex hierarchy of certificate authorities operated by the US government.

PIV cards were envisioned to function as “converged” credentials, combining physical access and logical access. They can be swiped or inserted into a badge-reader to open doors and gain access to restricted facilities. (In more low-tech scenarios reminiscent of how Hollywood depicts access checks, the automated badge reader is replaced by an armed sentry who casually inspects the card before deciding to let the intruders in.) But they can also open doors in a more virtual sense online: PIV cards can be inserted into a smart-card reader or tapped against a mobile device over NFC to leverage the credential online. Examples of supported scenarios:

- Login to a PC, typically using Active Directory and the public-key authentication extension to Kerberos

- Sign/encrypt email messages via S/MIME

- Access restricted websites in a web browser, using TLS client authentication.

This last capability creates an opening for remotely detecting whether someone has a PIV card— and by extension, affiliated with the US government or one of its contractors.

Background on TLS client authentication

Most websites in 2024 use TLS to protect the traffic from their customers against eavesdropping or tampering. This involves the site obtaining a digital certificate from a trusted certificate authority and presenting that credential to bootstrap every connection. Notably the customers visiting that website do not need any certificates of their own. Of course they must be able validate the certificate presented by that website, but that validation step does not require any private, unique credential accessibly only to that customer. As far as the TLS layer is concerned, the customer or “client” in TLS terminology, is not authenticated. There may be additional authentication steps at a higher layer in the protocol stack, such as a web page where the customer inputs their email address and password. But those actions take place outside the TLS protocol.

While the majority of TLS interactions today are one-sided for authentication, the protocol also makes provisions for a mode where both sides authenticate each other, commonly called “mutual authentication.” This is typically done with the client also presenting an X509 certificate. (Being a complex protocol TLS has other options including a “preshared key” model but those are rarely deployed.) At a high level, client authentication adds a few more steps to the TLS handshake:

- Server signals to the client that certificate authentication is required

- Server sends a list of CAs that are trusted for issuing client certificates. Interestingly this list can be empty, which is interpreted as anything-goes

- Client sends a certificate issued by one of the trusted anchors in that list, along with a signature on a challenge to prove that it is control of the associated private key

Handling privacy risks

Since client certificates typically contain uniquely identifying information about a person, there is an obvious privacy risk from authenticating with one willy-nilly to every website that demands a certificate. These risks have been long recognized and largely addressed by the design of modern web browsers.

A core privacy principle is that TLS client authentication can only take place with user consent. That comes down to addressing three different cases when a server requests a certificate from the browser:

- User has no certificate issued by any of the trust anchors listed by the server. In this case there is no reason to interrupt the user with UI; there is nothing actionable. Handshake continues without any client authentication. Server can reject such connections by terminating the TLS handshake or proceed in unauthenticated state. (The latter is referred to as optional mode, supported by popular web servers including nginx.)

- There is exactly one certificate meeting the criteria. Early web browsers would automatically use that certificate, thinking they were doing the user a favor by optimizing away an unnecessary prompt. Instead they were introducing a privacy risk: websites could silently collect personally identifiable information by triggering TLS client authentication and signaling that they will accept any certificate. (Realistically this “vulnerability” only affected a small percent of users because client-side PKI deployments were largely confined to enterprises and government/defense sectors. That said, those also happen to be among the most stringent scenarios where the customer cares a lot about operational security and privacy.)

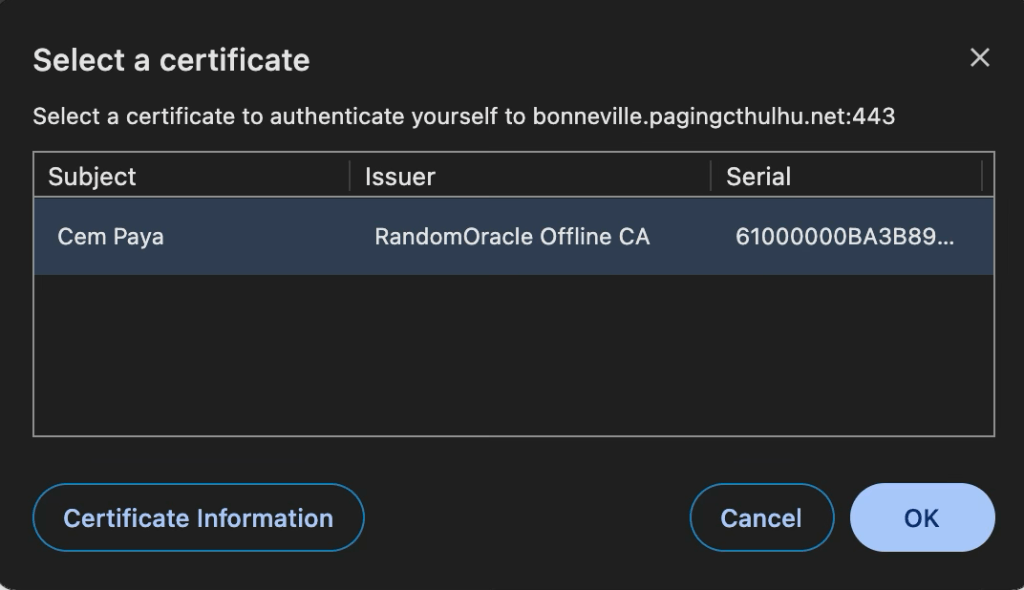

Browser designers have since seen the error of their ways. Contemporary implementation are consistent in presenting some UI before using the certificate. This is an important privacy control for users who may not want to send identifying information:

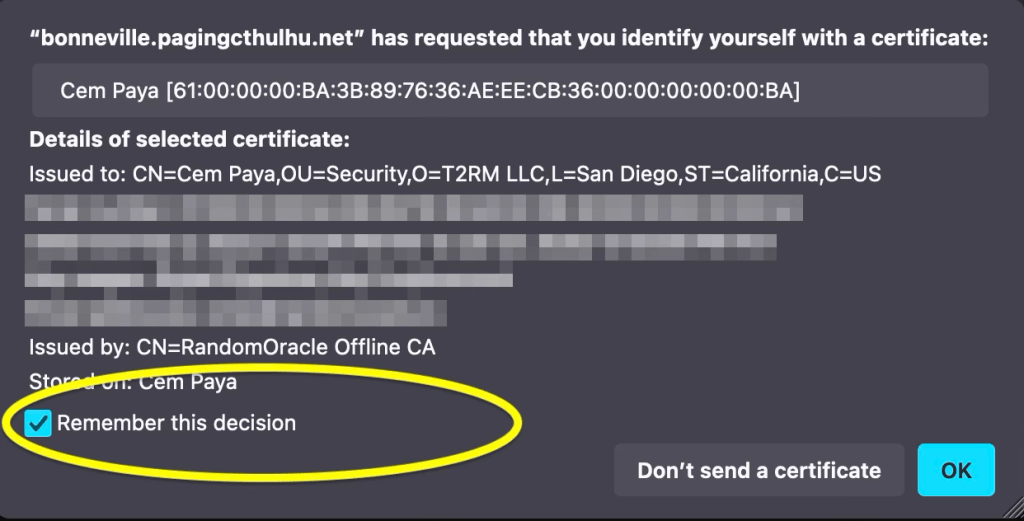

- There is still one common UX optimization to streamline this: users can indicate that they trust a website and are always willing to authenticate with a specific certificate there. Here is Firefox presenting a checkbox for making that decision stick:

- Multiple matching certificates can be used. This is treated identically as case #2, with the dialog showing all available certificate for the user to choose from, or decline authentication altogether.

Detecting the existence of a certificate

Interposing a pop-up dialog appears to address privacy risks from websites attempting to profile users through client certificates. While any website visited can request a certificate, users remain in control of deciding whether their browser will go along with. (And if the person complies and sends along their certificate to a website that had no right to ask? Historically browser vendors react to such cases with a time-honored strategy: blame the user— “PEBCAC! It’s their fault for clicking OK.”)

But even with the modal dialog, there is an information leak sufficient to enable shenanigans in the spirit of spot-the-Fed. There is a difference between case #1—no matching certificates— and remaining cases where there is at least one matching certificate. In the latter cases some UI is displayed, disrupting the TLS handshake until the user interacts with that UI to express their decision either way. In the former case, TLS connection proceeds without interruption. That difference can be detected: embed a resource that requires TLS client authentication and measure its load time.

While the browser is waiting for the user to make a decision, the network connection for retrieving the resource is stalled. Even if the user correctly decides to reject the authentication request, page load time has been altered. (If they agree, timing differences are redundant: the website gets far more information than it bargained for with the full certificate.) The resulting delay is on the order of human reaction times—the time taken to process the dialog and click “cancel”— well within the resolution limits of web Performance API.

Proof of concept: Spot-the-Fed

This timing check suffices to determine whether a visitor has a certificate from any one of a group of CAs chosen by the server. While the server will not find out the exact identity of the visitor— we assume he/she will cancel authentication when presented with the certificate selection dialog— the existence of a certificate alone is enough to establish affiliation. In the case of the US government PKI program, the presence of a certificate signals that the visitor has a PIV card.

Putting together a proof-of-concept:

- Collect issuer certificates for the US federal PKI. There are at least two ways to source this.

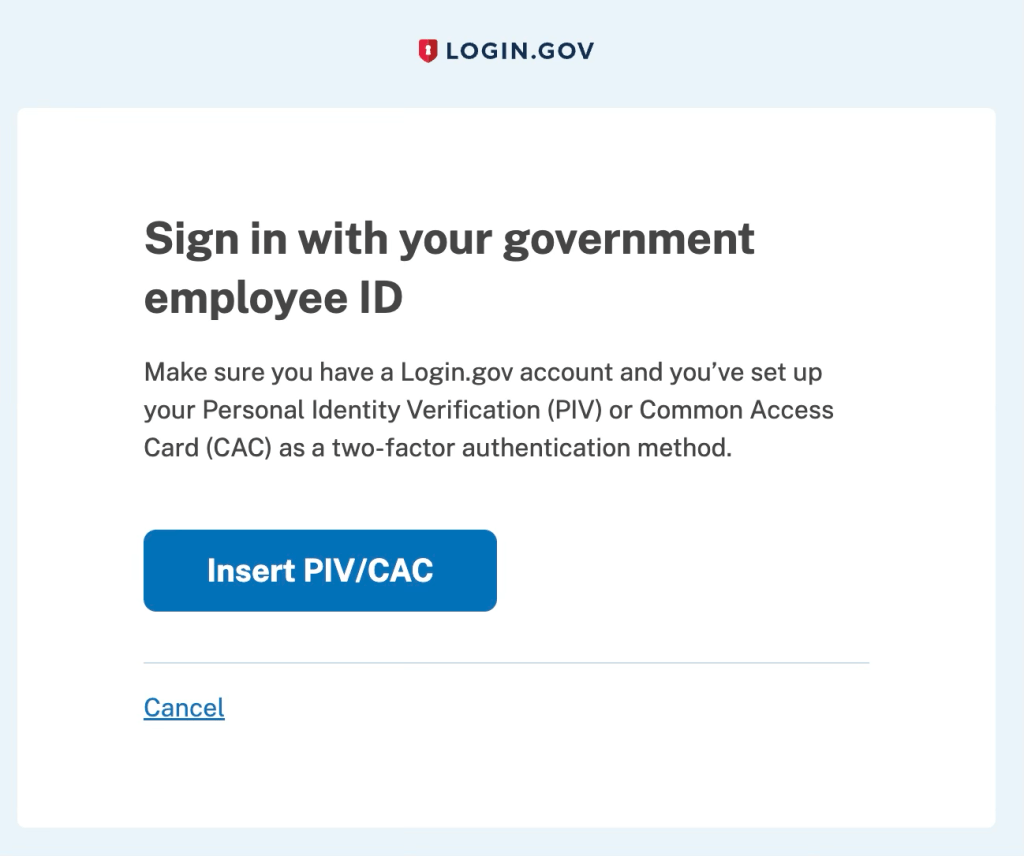

- Use a public site such as login.gov which accepts PIV cards via TLS client authentication. As the server conveniently enumerates all trusted issuers during the TLS handshake, we can simply copy that list.

- Download the certificate bundle from public sites. There are several options, including one official US government page on Github as well as personal sites with helpful information about CAC.

This turns out to result in a surprisingly large number of CAs, attesting to the sheer scale of the federal PKI infrastructure. There is an overview of the program and trust graph of CA structure on the official IDManagement website.

- Host a page on Github for the top-level document. It will include basic javascript to measure time taken for loading an embedded image that requires client authentication.

- Because Github Pages do not support TLS client authentication, that image must be hosted somewhere else. For example one can use nginx running on an EC2 instance to serve a one-pixel PNG image.

- Configure nginx for optional TLS client authentication, with trust anchors set to the list of CAs retrieved in step #1

There is one subtlety with step #4: nginx expects the full issuer certificates in PEM format. But if using option 1A above, only the issuer names are available. This turns out not to be a problem: since TLS handshake only deals in issuer names, one can simply create a dummy self-signed CA certificate with the same issuer but brand new RSA key. For example, from login.gov we learn there is a trusted CA with the distinguished name “C=US, O=U.S. Government, OU=DoD, OU=PKI, CN=DOD EMAIL CA-72.” It is not necessary to have the actual certificate for this CA (although it is present in the publicly availably bundles linked above); we can create a new self-signed certificate with the same DN to appease nginx. That dummy certificate will not work for successful TLS client authentication against a valid PIV card— the server can not validate a real PIV certificate without the real issuer public key of the issuing CA. But that is moot; we expect users will refuse to go through with TLS client authentication. We are only interested in measuring the delay caused by asking them to entertain the possibility.

Limitations and variants

Stepping back to survey what this PoC accomplishes: we can remotely determine if a visitor to the website has a certificate issued by one of the known US government certificate authorities. This check does not require any user interaction, but it also comes with some limitations:

- Successful detection requires that the visitor has a smart-card reader connected to their machine, their PIV card is present in that reader and all necessary middleware required to use that card is present. In practice, no middleware is required for the common case of Windows: PIV support has been built into the OS cryptography stack since Vista. Browsers including Chrome & Edge can automatically pick up any cards without requiring additional configuration. On other platforms such as MacOS and Linux additional configuration may be required. (That said: if the user already has scenarios requiring use of their PIV card on that machine, chances are it is already configured to also allow the card to work in the browser without futzing with any settings.)

- It is not stealthy in the case of successful identification. Visitors will have seen a certificate selection dialog come up. (Those without a client certificate however will not observe anything unusual.) That is not a common occurrence when surfing random websites. There are however a few websites (mis?)configured to demand client certificates from all visitors, such as this IP6 detection page.

- It may be possible to close the dialog without user interaction. One could start loading a resource that requires client authentication and later use javascript timers to cancel that navigation. In theory this will dismiss the pending UI. (In practice it does not appear to work in Chrome or Firefox for embedded resources, but works for top-level navigation.) To be clear, this does not prevent the dialog from appearing in the first place. It only reduces the time the dialog remains visible, at the expense of increased false-positives because detection threshold must be correspondingly lower.

- A less reliable but more stealthy approach can be built if there is some website the target audience frequently logs into using their PIV card. In that case the attacker can attempt to source embedded content from that site— such as an image— and check if that content loaded successfully. This has the advantage that it will completely avoid UI in some scenarios. If the user has already authenticated to the well-known site within the same browser session, there will be no additional certificate selection dialogs. That signals the user has a PIV card because they are able to load resources from a site ostensibly requiring a certificate from one of the trusted federal PKI issuer. In some cases UI will be skipped even if the user has not authenticated in the current session, but has previously configured their web browser to automatically use the certificate at that site, as is possible with Firefox. (Note there will also be a PIN prompt for the smart-card— unless it has been recently used in the same browser session.)

- While the PoC checks whether the user has a certificate from any one of a sizable collection of CAs, it can be modified to pinpoint the CA. Instead of loading a single image, one can load dozens of images in series from different servers each configured to accept only one CA among the collection. This can be used to better profile the visitor, for example to distinguish between contractors at Northrop Grumman (“CN=Northrop Grumman Corporate Root CA-384”) versus employees from the Department of Transportation (“CN=U.S. Department of Transportation Agency CA G4.”)

- There are some tricky edge-cases involving TLS session resumption. This is a core performance improvement built into TLS to avoid time-consuming handshakes for every connection. Once a TLS session is negotiated with a particular server—with or without client authentication— that session will be reused for multiple requests going forward. Here that means loading the embedded image a second time will always take the “quick” route by using the existing session. Certificate selection UI will never be shown even if there is a PIV card present. Without compensating logic, that would result in false-negatives whenever the page is refreshed or revisited within the same session. This demonstration attempts to counteract that by setting a session cookie when PIV cards are detected and checking for that cookie on subsequent runs. In case the PoC is misbehaving, try using a new incognito/private window.

Work-arounds

The root cause of this information disclosure lies with the lack of adequate controls around TLS client authentication in modern browsers. While certificates will not be used without affirmative consent from the consumer, nothing stops random websites from initiating an authentication attempt.

Separate browser profiles are not necessarily effective as a work-around. At first it may seem promising to create two different Chrome or Edge profiles, with only one profile used for “trusted” sites setup for authenticating with the PIV card. But unlike cookie jars, digital certificates are typically shared across all profiles. Chrome is not managing smart-cards; Windows cryptography API is responsible for that. That system has no concept of “profiles” or other boundaries invented by the browser. If there is a smart-card reader with a PIV card present attached, the magic of OS middleware will make it available to every application, including all browser profiles.

Interestingly using Firefox can be a somewhat clunky work-around because Firefox uses NSS library instead of the native OS API for managing certificates. While this is more a “bug” than feature in most cases due to the additional complexity of configuring NSS with the right PKCS#11 provider to use PIV cards, in this case it has a happy side-effect: it becomes possible to decouple availability of smart-cards on Firefox from Chrome/Edge. By leaving NSS unconfigured and only visiting “untrusted” sites with Firefox, one can avoid these detection tricks. (This applies specifically to Windows/MacOS where Chrome follows the platform API. It does not apply to Linux where Chrome also relies on NSS. Since there is a single NSS configuration in a shared location, both browsers remain in lock-step.) But it is questionable whether users can maintain such strict discipline to use the correct browser in every case. It would also cause problems for other applications using NSS, including Thunderbird for email encryption/signing.

Until there are better controls in popular browsers for certificate authentication, the only reliable work-around is relatively low-tech: avoid leaving a smart-card connected when the card is not being actively used. However this is impossible in some scenarios, notably when the system is configured to require smart-card logon and automatically lock the screen on card removal.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.