(Lessons from the ScreenConnect certificate-revocation episode)

An earlier blog post recounted the discovery of threat actors leveraging the ScreenConnect remote assistance application in the wild, and events leading up to DigiCert revoking the certificate previously issued to the vendor ConnectWise for signing those binaries. This follow-up is a deeper, more technical dive into a design flaw in the ScreenConnect executable that made it particularly appealing for malicious campaigns.

Trust decisions in an open ecosystem

Before discussing what went wrong with ScreenConnect, let’s cover the “sunny-day path” or how code-signing is supposed to work. To set context, let’s rewind the clock ~20 years, back to when software distribution was far more decentralized. Today most software applications are purchased through a tightly controlled app-store such as the one Apple operates for Macs and iPhones. In fact mobile devices are locked down to such an extent that it is not possible to “side-load” applications from any other source, without jumping through hoops. But this was not always the case and certainly not for the PC ecosystem. Sometime in the late 1990s with the mass adoption of the Internet, downloading software increasingly replaced the purchase of physical media. While anachronistic traces of “shrink-wrap licenses” survive in the terminology, few consumers were actually removing shrink-wrapping from a cardboard box containing installation CDs. More likely their software was downloaded using a web-browser directly from the vendor website.

That shift had a darker side: it was a boon for malware distribution. Creating packaged software with physical media takes time and expense. Convincing a retailer to devote scarce shelf-space to that product is an even bigger barriers. But anyone can create a website and claim to offer a valuable piece of software, available for nothing more than the patience required for the slow downloads over the meager “broadband” speeds of the era. Operating system vendors even encouraged this model: Sun pushed Java applets in the browsers as a way to add interactivity to static HTML pages. Applets were portable: written for the Java Virtual Machine, they can run just as well on Windows, Mac and 37 flavors of UNIX in existence at the time. MSFT predictably responded with a Windows-centric take on this perceived competitive threat against the crown jewels: ActiveX controls. These were effectively native code shared libraries, with full access to the Windows API. No sandboxing, no restrictions once execution starts. Perfect vehicle for malware distribution.

Code-signing as panacea?

Enter Authenticode. Instead of trying to constrain what applications can do once they start running, MSFT opted for a black & white model for trust decisions made at installation time based on the pedigree of the application. Authenticode was a code-signing standard that can be applied to any Windows binary: ActiveX controls, executables, DLLs, installers, Office macros and through an extensibility layer even third-party file formats although there were few takers outside of the Redmond orbit. (Java continued to use its own cross-platform JAR signing format on Windows, instead of the “native” way.) It is based on public-key cryptography and PKI, much like TLS certificates. Every software publisher generates a key-pair and obtains a digital certificate from one of a handful of trusted “certificate authorities.” The certificate associates the public-key with the identity of the vendor, for example asserting that a specific RSA public-key belongs to Google. Google can use its private-key to digitally sign any software it publishes. Consumers downloading that software can then verify the signature to confirm that the software was indeed written by Google.

A proper critique of everything wrong with this model— starting with its naive equation of “identified vendor” to “trusted/good” software you can feel confident installing— would take a separate essay. For the purposes of this blog post, let’s suspend disbelief and assume that reasonable trust decisions can be made based on a valid Authenticode signature. What else can go wrong?

Custom installers

One of the surprising properties about ScreenConnect installer is that the application is completely turnkey: after installation, the target PC is immediately placed under remote control of a particular customer. No additional configuration files to download, no questions asked of end users. (Of course this property makes ScreenConnect equally appealing for malicious actors as it does for IT administrator.) That means the installer has all the necessary configuration included somehow. For example it must know which remote server to connect for receiving remote commands. That URL will be different for every customer.

By running strings on the application, we can quickly locate this XML configuration.

For the malicious installer masquerading as bogus River “desktop app:”

This means ScreenConnect is somehow creating a different installer on-demand for every customer. The UI itself appears to support that thesis. There is a form with a handful of fields you can complete before downloading the installer. Experiments confirm that a different binary is served when those parameters are changed.

That would also imply that ConnectWise must be signing binaries on the fly. A core assumption in code-signing is a digitally signed application can not be altered without invalidating that signature. (If that were not true, signatures would become meaningless. An attacker can take an authentic, benign binary, modify it to include malicious behavior and have that binary continue to appear as the legitimate original. There have been implementation flaws in Authenticode that allowed such changes, but these were considered vulnerabilities and addressed by Microsoft.)

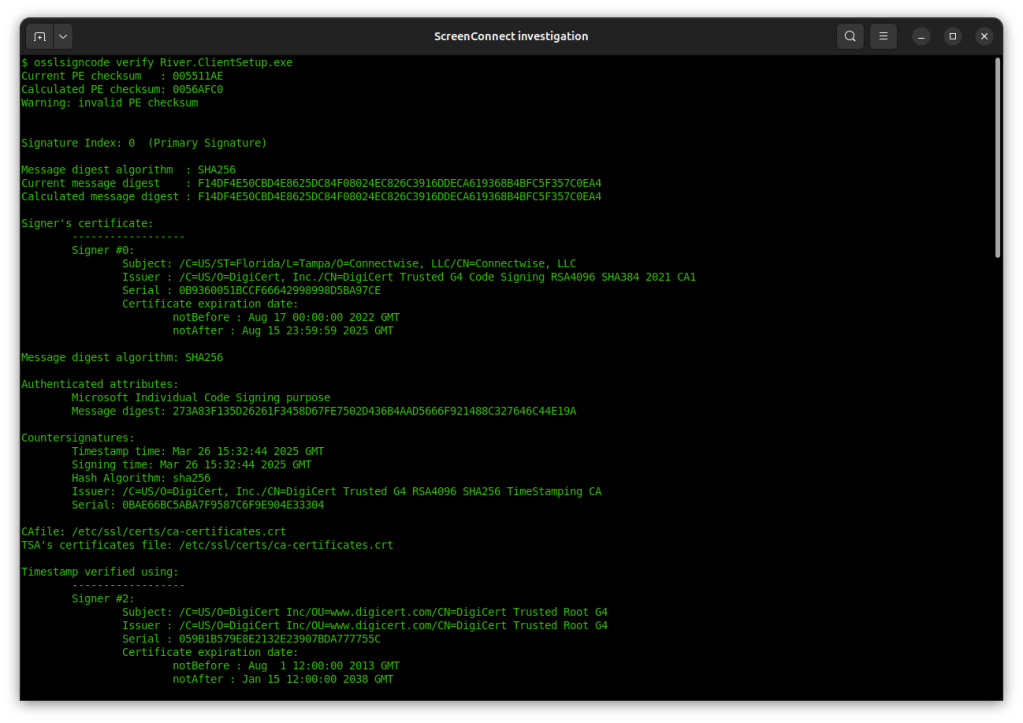

But using osslcode to inspect the signature in fact shows:

1. All binaries have the same timestamp. (Recall this is a third-party timestamp, effectively a countersignature, provided by a trusted-third party, very often a certificate authority.)

2. All binaries have the same hash for the signed portion

Misuse of unauthenticated attributes

That second property requires some explanation. In an ideal world the signature would cover every bit of the file— except itself, to avoid creating a self-referential. There are indeed some simple code-signing standards that work this way: raw signature bytes are tacked on at the end of the file, offloading all complexity around format and key-management (what certificate should be used to verify this signature?) to the verifier.

While Authenticode signatures also appear at the end of binaries, their format is on the opposite end of the spectrum. It is based on a complex standard called Cryptographic Message Syntax (CMS) which also underlies other PKI formats including S/MIME for encrypted/signed email. CMS defines complex nested structures encoded using a binary format called ASN1. A typical Authenticode signatures features:

- Actual signature of the binary from the software publisher

- Certificate of the software publisher generating that signature

- Any intermediate certificates chaining up to the issuer required to validate the signature

- Time-stamp from trusted third-party service

- Certificate of the time-stamping service & additional intermediate CAs

None of these fields are covered by the signature. (Although the time-stamp itself covers the publisher signature, as it is considered a “counter-signature”) More generally CMS defines a concept of “unauthenticated_attributes:” these are parts of the file not covered by the signature and by implication, can be modified without invalidating the signature.

It turns out ScreenConnect authors made a deliberate decision to abuse the Authenticode format. They deliberately place the configuration in one of these unauthenticated attributes. The first clue to this comes from dumping strings from the binary along with the offset where they occur. In a 5673KB file the XML configuration appears within the last 2 kilobytes— the region where we expect to find the signature itself.

The extent of this anti-pattern becomes clear when we use “osslsigncode extract-signature” to isolate the signature section:

$ osslsigncode extract-signature RiverApp.ClientSetup.exe RiverApp.ClientSetup.sig

Current PE checksum : 005511AE

Calculated PE checksum: 0056AFC0

Warning: invalid PE checksum

Succeeded

$ ls -l RiverApp.ClientSetup.sig

-rw-rw-r-- 1 randomoracle randomoracle 122079 Jun 21 12:35 RiverApp.ClientSetup.sig122KB? That far exceeds the amount of space any reasonable Authenticode signature could take up, even including all certificate chains. Using openssl pkcs7 subcommand to parse this structure reveals the culprit for the bloat at offset 10514:

There is a massive ~110K section using the esoteric OID “1.3.6.1.4.1.311.4.1.1” (The prefix 1.3.6.1.4.1.311 is reserved for MSFT; any OID starting with that prefix is specific to Microsoft.)

Looking at the ASN1value we find a kitchen sink of random content:

- More URLs

- Additional configuration as XML files

- Error messages encoded in Unicode (“AuthenticatedOperationSuccessText”)

- English UI strings as ASCII strings (“Select Monitors”)

- Multiple PNG image files

It’s important to note that ScreenConnect went out of its way to do this. This is not an accidental feature one can stumble into. Simply tacking on 110K at the end of the file will not work. Recall that the signature is encapsulated in a complex, hierarchical data structure encoded in ASN1. Every element contains a length field. Adding anything to this structure requires updating the length field for every enclosing element. That’s not simple concatenation: it requires precisely controlled edits to ASN1. (For an example, see this proof-of-concept that shows how to “graft” the unauthenticated attribute section from one ScreenConnect binary to another using the Python asn1crypto module.)

The problem with mutable installers

The risks posed by this design become apparent when we look at what ScreenConnect does after installation: it automatically grants control of the current machine to a remote third-party. To make matters worse, this behavior is stealthy by design. As discussed in the previous blog post, there are no warnings, no prompts to confirm intent and and no visual indicators whatsoever that a third-party has been given privileged access.

That would have been dangerous on its own— ripe for abuse if a ScreenConnect customers uses that binary for managing machines that are not part of their enterprise. At that point crosses the line from “remote support application” into “remote administration Trojan” or RAT territory. But the ability to tamper with configuration in a signed binary gives malicious actors even more leeway. They do not even need to be a ScreenConnect customer. All they need to do is get their hands on one signed binary in the wild. They can now edit the configuration residing in the unauthenticated ASN1 attribute, changing the URL for command & control server to one controlled by the attacker. Authenticode signature continues to validate and the tampered binary will still get the streamlined experience from Windows: one-click install without elevation prompt. But instead of connecting to a server managed by the original customer of ScreenConnect, it will now connect to the attacker command & control server to receive remote commands.

Resolution

This by-design behavior in ScreenConnect was deemed such high risk that the certificate authority (DigiCert) who issued ConnectWise their Authenticode certificate took the extraordinary step of revoking the certificate and invalidating all previously signed binaries. ConnectWise was forced to scramble and coordinate a response with all customers to upgrade to a new version of the binary. The new version no longer embeds critical configuration data in unauthenticated signature attributes.

While the specific risk with ScreenConnect has been addressed, it is worth pointing out that nothing prevents similar installers from being created by other software publishers. No changes have been made to Authenticode verification logic in Windows to reject extra baggage appearing in signatures. It is not even clear if such a policy can be enforced. There is enough flexibility in the format to include seemingly innocuous data such as extra self-signed certificates in the chain. For that matter, even authenticated fields can be used to carry extra information, such as the optional nonce field in the time-stamp. For the foreseeable future it is up to each vendor to refrain from using such tricks and creating installers that can be modified by malicious actors.

CP

Acknowledgments: Ryan Hurst for help with the investigation and escalating to DigiCert

You must be logged in to post a comment.