An unusual phishing site

In late May, the River security team received a notification about a new fraudulent website impersonating our service. Phishing is a routine occurrence that every industry player contends with. There are common playbooks invoked to take-down offending sites when one is discovered.

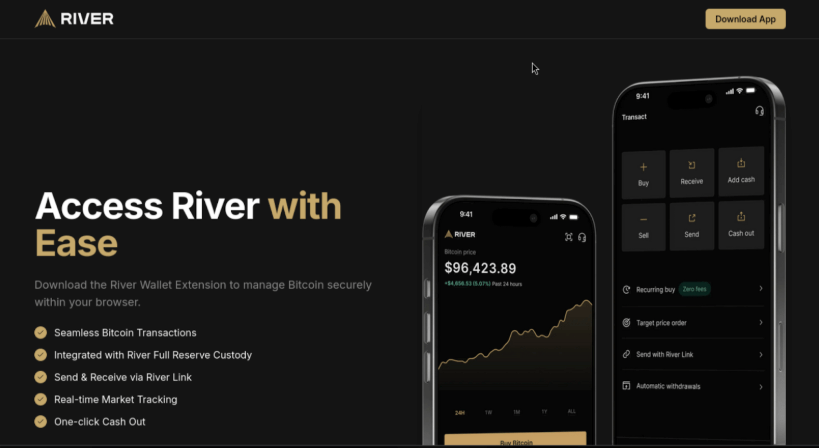

What made this case stand out was the tactic employed by the attacker. Most phishing pages go after credentials. They present a fraudulent authentication page that mimics the real one, asking for password or OTP codes for 2FA. Yet the page we were alerted about did not have any way to log in. Instead, it advertised a fake “River desktop app.” River publishes popular mobile apps for iOS and Android, but there has never been a desktop application for Windows, macOS, or Linux.

As this screenshot demonstrates, the home page was subtly altered to replace the yellow “Sign up” button on the upper-right corner with one linking to the bogus desktop application. We observed the site always serves the same Windows app, regardless of the web browser or operating system used to view the page. Google Chrome on macOS and Firefox on Linux both received the same Windows binary, despite the fact that it could not have run successfully on those platforms.

This looked like a bizarre case of a threat actor jumping through hoops to write an entire Windows application to confuse River clients. Native Windows applications are a rare breed these days— most services are delivered through web or mobile apps. The story only got stranger once we discovered the application carried a valid code signature.

Authentic malware

Quick recap on code signing: Microsoft has a standard called “Authenticode” for digitally signing Windows applications. These signatures identify the provenance and integrity of the software, proving authorship and guaranteeing that the application has not been tampered with from the original version as published. This is crucial for making trust decisions in an open ecosystem when applications may be sourced from anywhere, not just a curated app store.

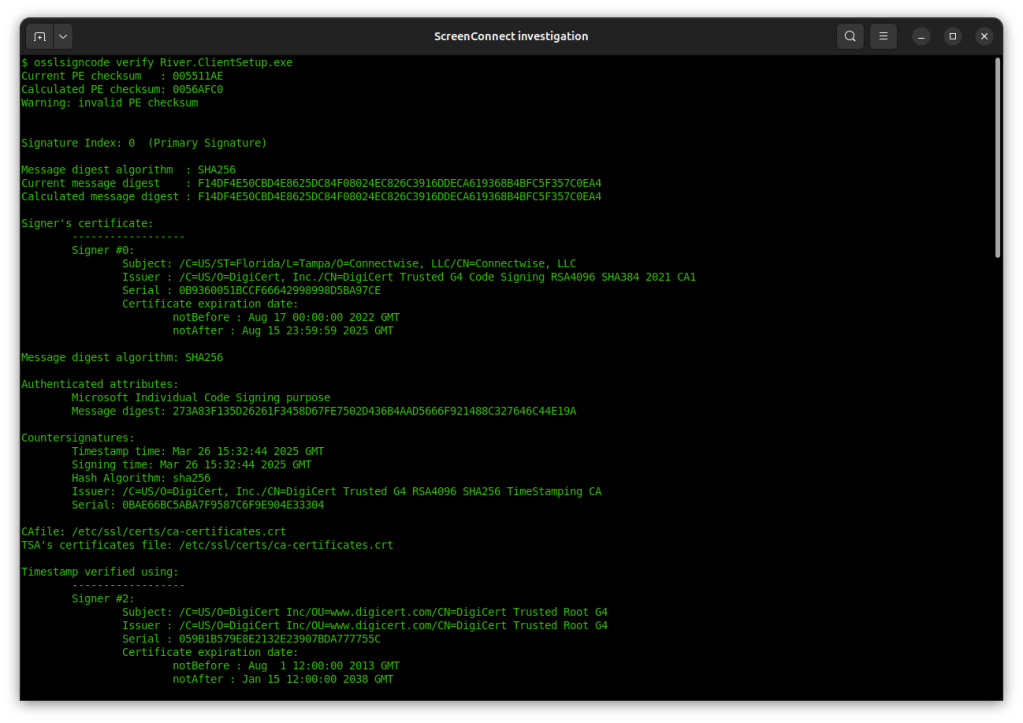

Authenticode signatures can be examined on non-Windows platforms using the open-source osslsigncode utility. This binary was signed by ConnectWise, using a valid certificate issued in 2022 from DigiCert:

Windows malware is pervasive, but malware bearing a valid digital signature is less common, and short-lived. Policies around code-signing certificates are clear on one point: if it is shown that a certificate is used to sign harmful code, the certificate authority is obligated to revoke it. (Note that code-signing certificates are governed by the same CAB Forum that sets issuance standards for TLS certificates, but under a different set of rules than the more common TLS use-case.)

ConnectWise is a well-known company that has been producing software for IT support over a decade. As it is unlikely for such a reputable business to operate malware campaigns on the side, our first theory was a case of key-compromise: a threat actor obtained the private keys that belonged to ConnectWise and started signing their own malicious binaries with it. This is the most common explanation for malware that is seemingly published by reputable companies: someone else took their keys and certificate. Perhaps the most famous case was Stuxnet malware targeting Iran’s nuclear enrichment program in 2010, using Windows binaries signed by valid certificates of two Taiwanese companies with no relationship to either the target or (presumed) attackers.

Looking closer at the “malware” served from the fraudulent website we were investigating, we discovered something even more bizarre: the attackers did not go to the trouble of writing a new application from scratch or even vibe-coding one with AI. This was the legitimate ScreenConnect application published by ConnectWise, served up verbatim, simply renamed as a bogus River desktop application.

That was not an isolated example. On the same server, we discovered samples of the exact same binary relabeled to impersonate additional applications, including a cryptocurrency wallet. We are far from being the first or only group to observe this in the wild. Malwarebytes noted social-security scams delivering ScreenConnect installer in April this year, and Lumu published an advisory around the same time.

Fine line between remote assistance and RAT

ScreenConnect is a remote-assistance application for Windows, Mac, and even Linux systems. Once installed, it allows an IT department to remotely control a machine, for example by deploying additional software, running commands in the background, or even joining an interactive screen-sharing session with the user to help troubleshoot problems.

Below is an example of what an IT administrator might see on the other side when using the server-side of ScreenConnect, either self-hosted or via a cloud service provided by ConnectWise.

At least this is the intended use case. From a security perspective, ScreenConnect is a classic example of a “dual-use application.” In the right hands, it can deliver a productivity boost to overworked IT departments, helping them deliver better support to their colleagues. In the wrong hands, it becomes a weapon for malicious actors to remotely compromise machines belonging to unsuspecting users. To be clear: ScreenConnect is not alone in this capacity. There are multiple documented instances of remote-assistances apps repurposed by threat actors at scale to remotely commandeer PCs of users they had no relationship with. But there are specific design decisions in the ScreenConnect installer as well as the application itself that greatly amplify the potential for abuse:

- The installation proceeds with no notice or consent. Because the binary carries a valid Authenticode signature, elevation to administrator privileges is automatic. Once elevated, there are no additional warnings or indications, nothing to help the consumer realize they are about to install a dangerous piece of software and cede control of their PC to an unknown third-party.

- Once installed, remote control takes effect immediately. No reboot required, no additional dialog asking users to activate the functionality.

- There is no indication that the PC is under remote management or that remote commands are being issued. For example, there is no system tray icon, notifications, or other visual indicators. (Compare this to how screen sharing— far less intrusive than full remote control— works with Zoom or Google Meets: users are given a clear indication that another participant is viewing their screen, along with a link to stop sharing any time.)

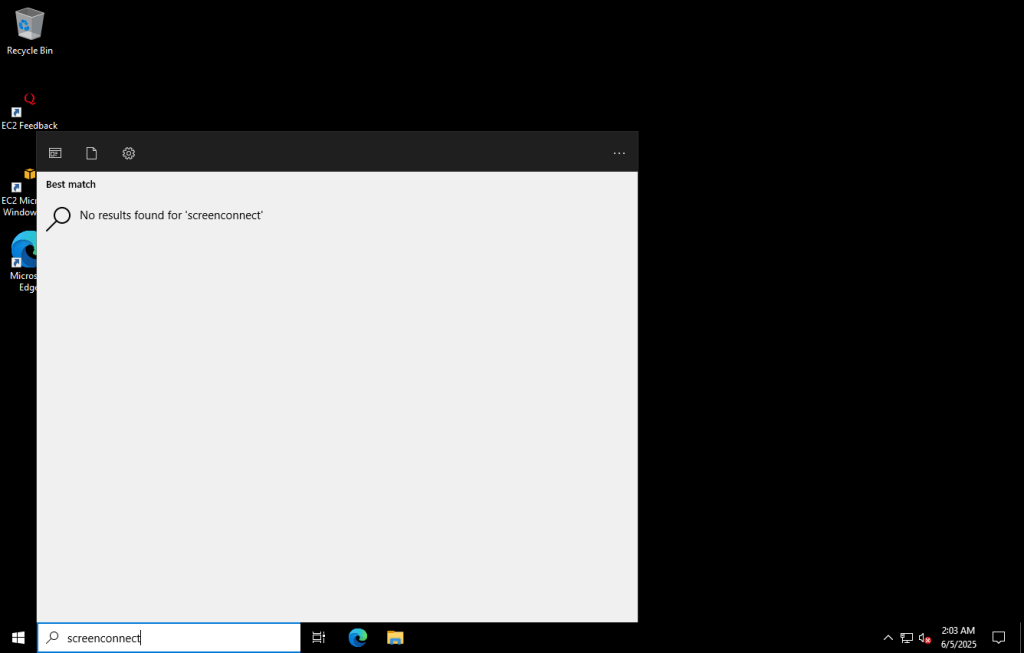

- There is no desktop icon or Windows menu entry created for ScreenConnect. For a customer who was expecting to get the River desktop app, it looks like the installation silently failed because their desktop looks the same as before. To understand what happened, users would have to visit the Windows control panel, review installed programs and observe that an unexpected entry called “ScreenConnect” has appeared there.

- Compounding these client-side design decisions, ScreenConnect was offering a 14-day free trial with nothing more than a valid email address required to sign up. [The trial page now states that it is undergoing maintenance— last visited June 15th.] A threat actor could take advantage of this opportunity to download customized installers such that upon completion, the machine where the installer ran will be under the control of that actor. (It is unclear if the threat actor impersonating River used a free trial with the cloud instance, or if they compromised a server belonging to an existing ScreenConnect customer. Around the same time, we found malware masquerading as a River desktop application, CISA issued a warning about a ScreenConnect server vulnerability being exploited in the wild.)

Disclosure timeline

- May 30: Emails sent to security@ aliases for ScreenConnect and ConnectWise. No acknowledgment received in response.

- We later determined that the company expects to receive vulnerability disclosures at a different email alias, and our initial reports did not reach the security team.

- Jun 1: Ryan Hurst helped escalate the issue to DigiCert and outlined why this usage of a code-signing certificate contravenes CAB Forum rules.

- Jun 2: DigiCert acknowledged receiving the report of our investigation.

- Jun 3: DigiCert confirms the certificate has been revoked.

- Initial revocation time was set to June 3rd. Because Authenticode signatures also carry a trusted third-party timestamp, it is possible to revoke binaries forward from a specific point in time. This is useful when a specific key-compromise date can be identified: all binaries time-stamped before that point remain valid, all later binaries are invalidated. The malicious sample found in the wild masquerading as a River desktop app was timestamped March 20th. The most recent version of the ScreenConnect binary obtained via the trial subscription bears a timestamp of May 20th. Setting the revocation time to June 3rd has no effect whatsoever on validity of existing binaries in the wild, including those repurposed by malicious actors.

- Jun 4: DigiCert indicates the revocation timestamp will be backdated to issuance date of the certificate (2022) once ConnectWise has additional time to publish a new version.

- Jun 6: The ConnectWise security team gets in contact with River security team.

- Jun 9: ConnectWise notifies customers about an impending revocation, stating that installers must be upgraded by June 10th.

- Jun 10: ConnectWise extends deadline to June 13th.

- Jun 13: Revocation timestamp backdated to issuance by DigiCert, invalidating all previously signed binaries. This can be confirmed by retrieving the DigiCert CRL and looking for the serial ID of the ConnectWise certificate:

$ curl -s "http://crl3.digicert.com/DigiCertTrustedG4CodeSigningRSA4096SHA3842021CA1.crl" | openssl crl -inform DER -noout -text | grep -A4 "0B9360051BCCF66642998998D5BA97CE"

Serial Number: 0B9360051BCCF66642998998D5BA97CE

Revocation Date: Aug 17 00:00:00 2022 GMT

CRL entry extensions:

X509v3 CRL Reason Code:

Key CompromiseAcknowledgements

- Ryan Hurst for help with the investigation and recognizing how this scenario represented a divergence from CAB Forum rules around responsible use of code-signing certificates. While we were not the first to spot threat actors leveraging ScreenConnect binaries in the wild, it was Ryan who brought this matter attention to the attention of the one entity— DigiCert, the issuing certificate authority— in a position to take decisive action and mitigate the risk.

- DigiCert team for promptly taking action to protect not only River clients, but all Windows users against all potential uses of the ScreenConnect fraudulently mislabeled as another legitimate application.

Matt Ludwigs & Cem Paya, for River Security Team