This is a story about accidentally stumbling on a trivial exfiltration path out of an otherwise locked-down environment. Our setting is a multi-national enterprise with garden-variety Windows-centric IT infrastructure with one modern twist: instead of physical workstations on desks or laptops, employees are issued virtual desktops. They connect to these Windows VMs to work from anywhere, getting a consistent experience whether they are physically situated in their own assigned office location, visiting one of the worldwide locations or from the comfort of their home— a lucky break that allowed for uninterrupted access during the pandemic.

Impact of virtualization

Virtualization makes some problems easier. It is an improvement over issuing employees laptops that leave the premises every night and can be used in the privacy of an employee residence without any supervision. Laptops walk out the door every night, can be stolen, stay offline for extended periods without security updates, connect to dubious public networks or interface with random hardware— printers, USB drives, docking stations, Bluetooth speakers— all of which create more novel ways to lose company data resident on that device. These risks are not insurmountable; there are well-understood mitigations for managing each one. For example, full-disk encryption can protect against offline recovery from disk in case of theft. But each one must be addressed by the defenders. Virtual desktops are immune from entire classes of attacks applicable to physical devices that can wander outside the trusted perimeter.

But virtualization can also introduce complications into other classic enterprise security challenges. Data leak prevention or DLP is one this particular firm greatly obsessed about. Most modern startups are far more concerned about external threat actors trying to sneak inside the gates and rampage through precious resources inside the perimeter. Businesses founded on intellectual property prioritize a different threat model: attackers already inside the perimeter moving confidential corporate data outside. Usually this is framed in the context of insider malfeasance: rogue employees jumping ship to a competitor trying to take some of the secret sauce with them. But under a more charitable interpretation, it can also be viewed as defense-in-depth against an external attacker who compromises the account of an otherwise honest insider, with the intention of rummaging through corporate IP. In all cases, defenders must focus on all possible exfiltration paths— avenues for communicating with the “outside world”— and implement controls on each channel.

Sure enough, the IT department spent an inordinate amount of time doing exactly that. For example, all connections to the Internet are funneled through a corporate proxy. When necessary that proxy executes a man-in-the-middle attack on TLS connections to view encrypted traffic. (No small irony that activity that would constitute criminal violation of US wiretap statutes in a public setting has become standard practice for IT departments that are possesses of a particular mindset around network security.) This setup affords both proactive defense and detection after the fact:

- Outright block connections to file-sharing sites such as Dropbox and Box to prevent employees from uploading company documents to unsanctioned locations. (Dreaded “shadow IT” problem.)

- Even for sites with permitted connection, log all history of connections, type of HTTP activity (GET vs POST vs PUT) including hash of the content exchanged. This allows identifying an employee after the fact if he/she goes on an upload spree to copy company IP from the internal environment to a cloud service.

Rearranging deck chairs

In other ways virtualization does not change the nature of risk but merely reshuffles it downstream, to the clients used for connecting to the machine where the original problem used to live.

This enterprise allowed connections from unmanaged personal devices. It goes without saying there will be little assurance about the security posture of a random employee device. (Despite the long history of VPN clients trying to encroach into device-management under the guise of “network health checks,” where connections are only permitted for clients devices “demonstrating” their compliance with corporate policies.) One way to solve this problem is by treating the remote client as untrusted: isolate content on the virtual desktop as much as possible from the client, effectively presenting a glorified remote GUI.

There is a certain irony here. Remote desktop access solutions have gotten better over time at supporting more integration with client-side hardware. For example over the years Microsoft RDP has added support to:

- Share local drives with the remote machine

- Use a locally attached printer to print

- Allow local smart-cards to be used for logging into the remote system

- Allow pasting from local clipboard to the remote machine, or vice verse by pasting content from the remote PC locally

- Forward any local USB device such as webcam to the remote target

- Forward local GPUs to the remote device via RemoteFX vGPU

These are supposed to be beneficial features: they improve productivity when using a remote desktop for computing. Yet they become trivial exfiltration vectors in the hands of a disgruntled employee trying to take corporate IP off their machine.

The mystery NIC

Fast forward to an employee connecting to their virtual desktop from home. Using the officially sanctioned VPN client and remote-desktop software anointed by the IT department, this person logs into their work PC as usual. Later on in the session, an unexpected OS notification appears regarding the discovery of an unknown network. That innocuous warning in fact signals a glaring oversight in exfiltration controls.

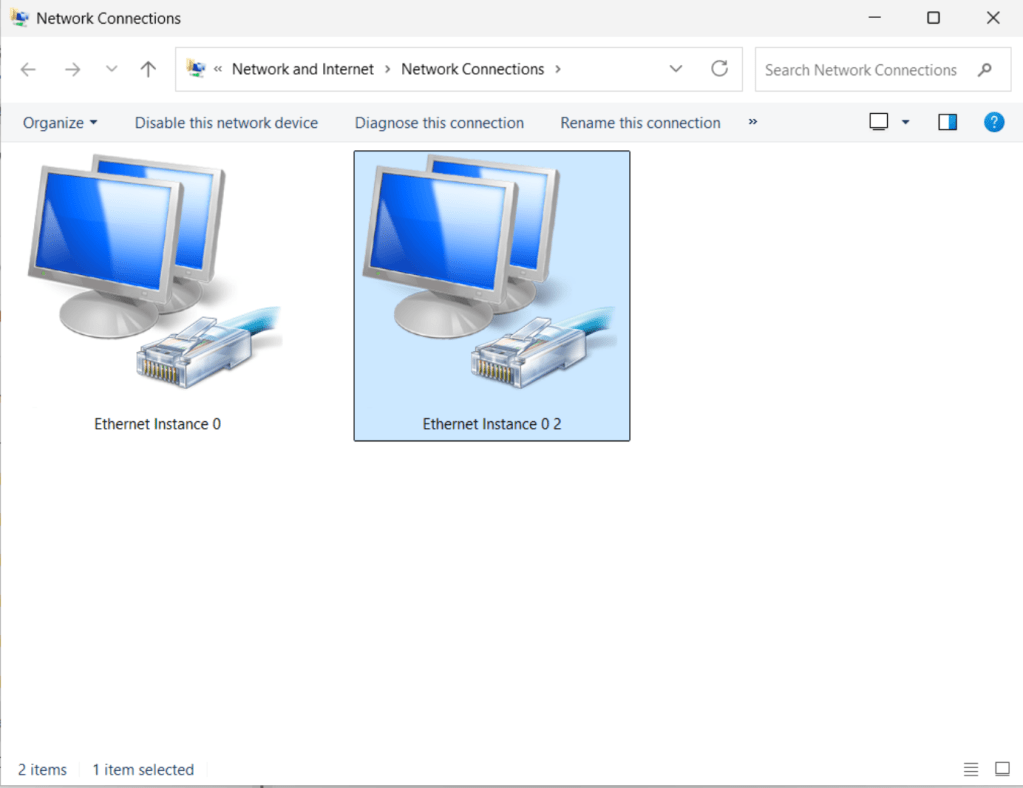

Peeking at “Network Connections” in Control Panel confirms the presence of a second network interface:

The appearance of the mystery NIC can be traced to an interaction between two routine actions:

- The employee connected their laptop to a docking station containing an Ethernet adapter. This is not an uncommon setup, since docking allows use of a larger secondary monitor and external keyboard/mouse for better ergonomics.

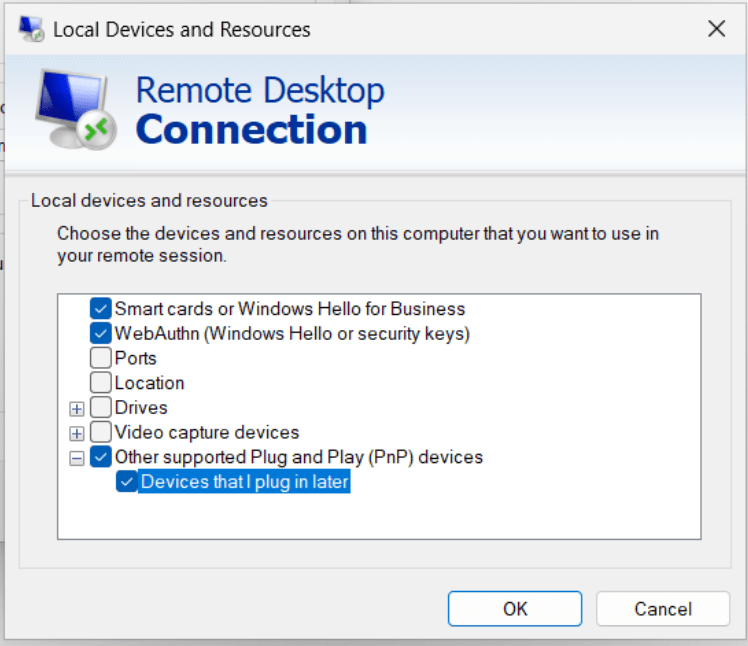

- Remote-desktop client was configured to forward newly connected USB devices to the remote server. This is also a common setup, to better single out devices that are intended for redirection by the explicit action of plugging them in after the session is created.

The second point requires some qualifications. While arbitrary USB forwarding over RDP is clearly risky, it is necessary to forward some classes of devices. For instance, video conferencing requires a camera and microphone. Virtual desktops do not have any audio or video devices of their own. (Even if such emulated devices did exist and received synthetic A/V feeds, they would be useless for the purpose of projecting the real audio/video from the remote user.) That makes a blanket ban against all USB forwarding infeasible. Instead defenders are forced to carefully manage exceptions by device class.

It turns out in this case the configuration was too permissive: it allowed forwarding USB network adapters.

Free for all

On the remote side, once Windows detects the presence of an additional USB device, plug-and-play (once derided as plug-and-pray) works its magic:

- Device class is identified

- Appropriate device driver is loaded. There was an element of luck here in that the necessary driver was already present out-of-the-box on Windows, avoiding the need to search/download the driver via Windows Update. (This is still automatically done by Windows, for drivers that have passed WHQL certification.)

- Network adapter is initialized

- DHCP is used to acquire an IP address

Depending on group policy, some security controls continue to apply to this connection. For example the Windows firewall rules will still be in effect and can prevent accepting connections. But anything else not explicitly forbidden by policy will work. This is an important distinction. It turns out the reason many obvious exfiltration paths fail in the standard enterprise setup is an accident of network architecture, instead of deliberate endpoint controls. For instance, users can not connect to a random SMB share on the Internet because there is no direct route from the internal corporate network. By contrast mounting file-shares work just fine inside the trusted intranet environment; the difference is one of reachability. Similar observations apply to outbound SSH, SFTP, RDP and all other protocols except HTTP/HTTPS. (Because web access is critical to productivity, almost every enterprise fields dedicated forward proxies to sustain the illusion that every server on the Internet can be accessed on ports 80/443.) Most enterprises will not restrict connections using these protocols because of an implicit assumption that any host reachable on those ports is part of the trusted environment.

A secondary network interface changes that, opening another path for outbound connections. This one is no longer constrained by the intranet setup assumed by the IT department. Instead it depends on the network that Ethernet-to-USB adapter is attached to— one that is controlled by the adversary in this threat model. In the extreme case, it is wide open to connections from the internet. More realistically the virtual desktop will appear as yet another device on the LAN segment of a home network. In that case there will be some restrictions on inbound access but nothing preventing outbound connections.

Exfiltration possibilities are endless:

- Hard-copies of documents can be printed to a printer on the local network

- Network drives such as NAS units can be mounted as SMB shares, allowing easy drag-and-drop copy from virtual desktop.

- To stay under the radar, one can deploy another device on the local network to act as an SFTP server. On the virtual desktop side, an SFTP client such as putty or Windows’ own SSH client (standard on recent Win10/11 builds) can then upload files to that server. While activity involving file-shares and copying via Windows tends to be closely watched by resident EDR software, SFTP is unlikely to leave a similar audit trail.

- For those committed to GUI-based solutions, outbound RDP also works. One could deploy another Windows machine with remote access enabled on the home network, to act as the drop point for files. Then an RDP connection can be initiated from the virtual desktop, sharing the C:\ drive to the remote target. This makes the entire contents of the virtual desktop available to the unmanaged PC. While inbound RDP is disallowed from sharing drives, there are typically no such restrictions on outbound RDP— yet another artifact of the assumption that such connections can only work inside the safe confines of trusty intranet, where every possible destination is another managed enterprise asset.

- For a much simpler but noisier solution, vanilla cloud-storage sites (Box, Dropbox, …) will also accessible through the secondary interface. When connections are not going through the corporate proxy, rules designed to block file-sharing sites have no affect. Since most of these website offer file uploads through the web browser, no special software or dropping to a command line is required.

- Caveat: It may take some finessing to get existing software on the remote desktop to use the second interface. While command line utilities such as curl will accept arguments to specify a particular interface used for initiating connections, browsers rarely expose that level of control.

These possibilities highlight a general point about the attackers’ advantage when it comes to preventing exfiltration from a highly connected environment. When a miss is as good as a mile, the fragility (futility?) of DLP solutions should ask customers to question whether this mitigation can amount to anything more than bureaucratic security theater.

CP