Reversing irreversibility and censorship-resistance

Stablecoins have made a major stride towards legitimacy with the signing of the GENIUS Act. That makes it a good time to visit some of the more surprising ways stablecoins differ from their underlying blockchain.

Two commonly cited advantages of blockchains are:

- Censorship resistance. By virtue of being a decentralized system, there is no government regulator or other authority in a position to decide who can transact on chain. It is not possible to “seize” funds or systemically exclude disfavored persons from the financial system.

- Irreversible transactions. Once the transaction is confirmed, it can not be undone. Unlike credit cards payments or ACH transfers, there are no disputes, no charge-backs or other avenues to claw back funds.

Whether these are features or bugs is in the eye of the beholder. Empowering individuals excluded from the banking system for politically reasons sounds noble— until that individual turns out to be Kim Jong-Un trying to finance a rogue nuclear weapons program. Likewise, finality in payments may seem very appealing to anyone accepting credit cards today. It is well known that scammers can pay for goods with a credit card and later contest the transaction in bad faith. That leaves the merchant holding the bag by default, or at least with the burden of proving that the buyer did indeed receive the services they were charged for. That may look like a raw deal for the merchant but consumers appreciate the value of such reversible transactions when they experience theft of digital assets, only to be told by their exchange/custodian that nothing can be done to recoup their losses.

Putting aside value judgments on irreversibility, there is one little-noted fact about stablecoin transactions: they are neither censorship-resistant or irreversible as a matter of necessity. This may come as a surprise. Stablecoins are built on top of blockchains lauded for having exactly those properties. Indeed it takes all the complexity of smart-contracts and virtual machines to “solve” that problem and create a centralized, tightly supervised digital asset class on top of an inherently decentralized, permissionless foundation.

No free lunch: in stablecoin issuers we trust

Stablecoins are an example of “real world assets on-chain.” Their distinguishing feature is being convertible one-to-one to a fiat currency such as the dollar or euro. By design blockchains are hermetically sealed systems: they have no direct interactions with the banking system or any other payment network. That makes it difficult to represent ownership of arbitrary assets in the real-world. This is where stablecoin issuers enter the picture: the issuer is the trusted third-party guaranteeing convertibility between the real world asset and its on-chain representation. Send dollars to the issuer and they will “mint” an equivalent amount of the stablecoin token and credit it to your blockchain address. Going in the other direction, participants may also choose to exit the system, exchanging their tokens for dollars. In that case the issuer execute a “burn,” taking out the equivalent quantity of tokens from circulation and returns the corresponding dollars back via traditional rails, such as wire transfer.

In practice, the stablecoin issuer does not have direct business relationships with every retail investor— that could not scale. Mints/burns are initiated by a relatively small number of intermediaries in the ecosystem, such as cryptocurrency exchanges. These intermediaries make it seamless for their customers to switch back and forth between fiat currency and stablecoins, while hiding the complexity of interactions with the issuer. Depending on the arrangement, they could also charge fees for the convenience or alternatively collect incentive payments from the issuer. Stablecoin issuance is a lucrative business, especially in a high interest regime. The issuer gets to collect interest on the fiat held in reserve. Since every dollar worth of stablecoin on chain requires a dollar held in an account by the issuer (for convertibility to work) the issuers profits correlate directly with the total outstanding amount in circulation. Conversely, it is a lousy deal for anyone to hold stablecoin when they could instead park the equivalent amount in fiat and collect the interest themselves.

In a 2001 essay titled “Trusted third-parties are security holes,” Nick Szabo called out the risks created by outsourcing critical roles in financial systems to allegedly trusted entities such as credit-card networks or certificate authorities. While this argument predated the rise of Bitcoin by several years, its warnings are prescient in the context of stablecoins. The convertibility of stablecoins to their underlying fiat currency is not guaranteed by any intrinsic property of blockchains. It does not matter that how decentralized the systems is and how well its consensus protocol as executed by thousands of independent nodes provides security against lone actors from disrupting the system. When it comes to stablecoins, it is 100% up to a single actor in the system—the stablecoin issuer— to link virtual dollars on-chain to real world dollars in a bank account.

It is easy to imagine ways that link can fail:

- The issuer can embezzle funds and vanish.

- It can deliberately issue more stablecoins than are held in reserves. That is, issue excess supply tokens without any fiat backing. Absent independent audits, the discrepancy could remain undetected for a long time, until some financial crisis results in a “run” with everyone trying to withdraw fiat out of the system, only to discover that the issuer cannot meet all redemptions.

- That same situation can arise due to incompetence instead of malfeasance: the issuer may experience a security breach of their systems. If a threat actor gains control of the on-chain “money printer” they can mint new tokens for their own benefit without any fiat backing.

- Instead of investing the reserves in low-risk assets such as treasuries, the issuer can roll the dice with dubious schemes and lose money, once again resulting in net deficit of fiat against virtual token.

All these cases lead to the same outcome: the stablecoin is no longer “full-reserve.” If all participants tried to convert back to the underlying currency, some of them would not get paid in full. Until recently, none of this was helped by the opacity of issuers operating in the Wild West of finance. In particular Tether, by far the largest issuer of dollar stablecoins with more than $100B outstanding, has been at the center of multiple controversies over its reserves and inconsistent statements. That includes a finding by NY state that at least during one stretch of time Tether was not fully backed. Time will tell if the newly enacted GENIUS legislation in the US will change this state of affairs and compel more transparency out of issuers.

For the remainder of this blog post, we put aside the ongoing shenanigans at Tether and focus on a hypothetical issuer that maintains full fiat backing of their assets, prudent in investing that fiat and competent at protecting against security threats. What are the risks posed by this ideal trusted third party?

Censorship-friendly by design

The surprising answer is that for virtually all major stablecoins in existence, this issuer retains the discretion to engage in arbitrary censorship and asset seizure. In order from mild to severe in their effects, these capabilities include:

- Preemptively block any address from participating in stablecoin transactions— effectively a form of debanking

- Freeze funds at any address. This goes one step further than mere debanking; now the issuer is temporarily preventing a network participant from accessing existing funds. Freezes can be lifted but in the worst-case scenario funds can remain accessible indefinitely.

- Burn funds at any address. We are now fully in asset-seizure territory. Unlike a temporary freeze on assets which may be lifted, this one is irreversible from the perspective of the participant whose funds are gone.

As a corollary to #3: stablecoin issuers may be in a position to reverse transactions. Imagine Alice sends Bob some stablecoins. This is handled by decreasing the balance for Alice’s address on the stablecoin ledger and incrementing the balance for Bob’s address by an identical amount. If Alice later disputes the transaction and the issuer sides with Alice they can simply burn the assets at Bob’s address and magically mint an equivalent amount at Alice’s source address. Presto: the funds Alice sent are restored and the ones Bob received are gone, reverting to the state before the transaction. This legerdemain has no effect on whether the stablecoin remains fully backed 1:1 by equivalent fiat reserves. No actual dollars or euros have left the system; instead their virtual representation on chain has been reshuffled to Alice’s benefit and at the expense of Bob.

Stablecoins under the hood

To appreciate the how this works, we need to establish a few facts about how stablecoins are implemented at the nuts-and-bolts level. From an engineering view stablecoin is nothing more than a special type of smart-contract operating on a contract-capable blockchain that manages its own ledger of balances. “Smart-contract” is a fancy way of saying glorified software: program or code. Due to the severe resource restrictions in the type of computations most blockchains can execute, these programs are quite rudimentary compared to a typical mobile app or moderately complex interactive website. (Constrained computing resources should not be confused with simplicity; being rudimentary has not stopped these applications from having catastrophic bugs that are exploited for millions of dollars in losses routinely.)

Not every contract represents a stablecoin. Stablecoins conform to a specific template, a least-common denominator that determines the functionality expected. Often these are standardized on a given chain. For example Ethereum has ERC-20. That specification defines the set of functions every contract representing a “fungible token” must implement. Again not every “fungible token” is a stablecoin: some represent a utility token that in theory can be used to pay for certain services on-chain. (Or so the theory went in 2017 when ICOs were all the rage for funding early-stage projects, by selling tokens ahead of time before the service in question was event built.)

For example looking at the ERC20 standard, we observe a number of functions that every stablecoin must support. Here are some of the most important ones associated with moving funds:

transfer: Sends funds to an address.approve: Pre-approve a specific address to be able to withdraw from the caller’s account up to specified amount. This is useful for smart-contract interactions— such as placing an order at a decentralized exchange— when the exact amount to be withdrawn can not be predicted in advance.transferFrom: Variant of transfer used by smart-contracts, in conjunction with the preapproval mechanism.

Oddly there is nothing in the standard about supervisory functions reserved for the issuer: minting new assets on chain, burning or withdrawing assets from circulation, much less blocking specific addresses or seizing assets. Where is that functionality? The answer is it is considered out of scope for ERC-20 standard. In software engineering terminology, it would be called an “implementation detail” that each contract is free to sort out for itself. Strictly speaking one could deploy a stablecoin that does not have any way to seize funds. Yet it is telling that all major stablecoins to date including Circle, Paxos, Gemini Dollar and even Tether have opted for building this functionality. [Full disclosure: this blogger was involved in the development of GUSD]

Case study: Circle

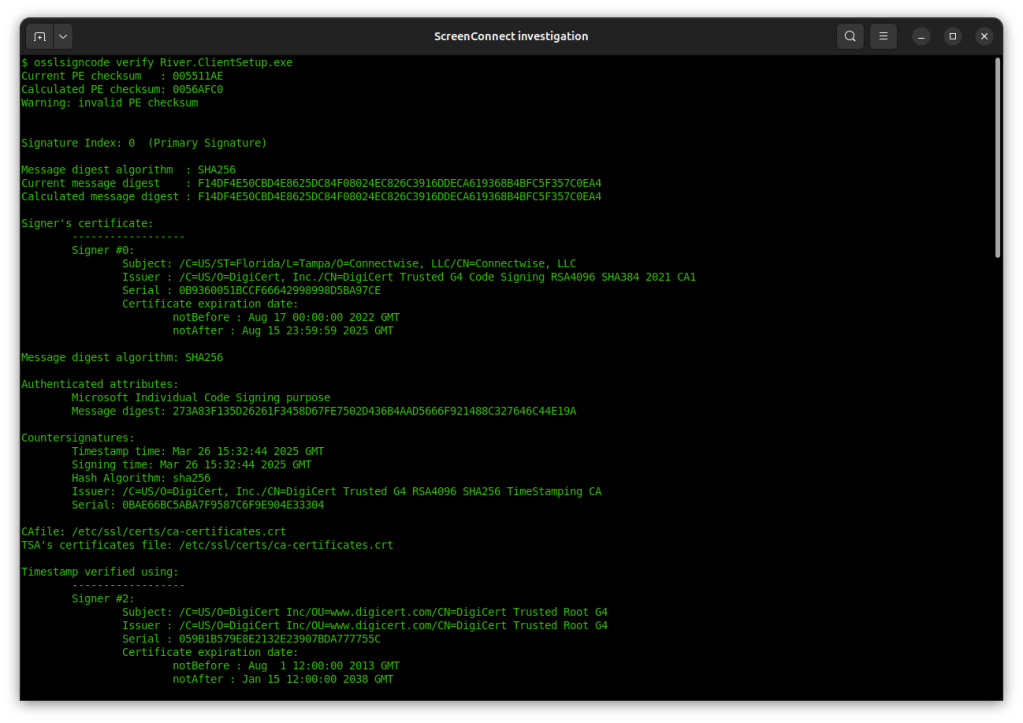

Let’s take a look at the smart-contract for the Circle stablecoin or USDC. Etherscan shows the token with ticker USDC is managed by the contract at address 0xa0b86991c6218b36c1d19d4a2e9eb0ce3606eb48. That page shows the contract has a verified source code; that means someone has uploaded source code which when compiled with a specific version of the Solidity compiler, produces EVM bytecode identical to what exists at that address. (Effectively a deterministic build process for proving that a given piece of code really does correspond to a deployed contract.) But this verified code is decidedly underwhelming, with hardly any indication of stablecoin functionality. That is because the Circle contract is just a thin proxy, a wrapper that forwards all incoming calls to an underlying secondary contract. This level of indirection is common to complex contracts on Ethereum. It allows upgrading what is otherwise immutable logic. While the proxy code can not be modified, the target contract it forwards to is just an ordinary data field that can be modified to point to a new address when it is time to upgrade the contract. (Strictly speaking, Ethereum now has a way to upgrade contracts in-place but the proxy pattern provides more control and transparency over the process. Here )

For our purposes, finding the actual implementation of USDC requires going one level deeper and chasing the value of that initial pointer. Etherscan makes this easy, as the constructor arguments already have a helpfully named argument called “implementation” which points to another verified contract that contains the real USDC stablecoin logic. This allows us to chase down the original implementation that the contract was deployed with.

Here is the functionality for freezing an address in a function appropriately called “blacklist:”

function blacklist(address _account) public onlyBlacklister { blacklisted[_account] = true; emit Blacklisted(_account);}Once an address is marked as blacklisted, all other operations involving that address in any capacity fail. It would come as no surprise that assets can not be transferred out of that address, but it is not even possible to send funds to that address as destination.

That function to mark an address as blacklisted is gated by the modifier onlyBlacklister. In the Solidity programming language, modifiers signal that some function can only be invoked when specific conditions are met. Modifiers themselves are defined by functions returning a boolean true/false indication. In the same source code listing, we can locate that function in a parent class inherited by the stablecoin:

modifier onlyBlacklister() { require(msg.sender == blacklister); _;}Translation: this function checks that the Ethereum address of the caller is identical to a predefined “blacklister” address. Not surprisingly, the blacklisting capability is not publicly available for any random person to invoke. It can only be called by a specific designated address. So who is the privileged blacklister?

Etherscan also allows inspecting internal contract state, including the values of internal variables. For example we can observe what the current the initial V1 deployment of the contract, the blacklister address was identical to the “master-minter” address authorized to issue new USDC on chain— presumably Circle itself.

Outsourcing censorhip

While minting and blacklisting address were one and the same in this example, it is worth exploring the consequence of the inherent flexibility in the contract to separate them. Blacklisting role can be outsourced to a third-party who specializes in blockchain compliance. Stablecoin issuers are already leveraging services such as Chainalysis, Elliptic and TRM for oversight of their network. In an alternative operational mode, they could just assign the blacklisting role to one of those service providers. For that matter, in a slightly more dystopian alternate universe, a government regulator could demand the role for itself.

Recall that the pointer-to-implementation pattern allow upgrading contract logic. Indeed the code linked above is not the current version of USDC. It has already gone through multiple iterations. The latest version deployed as of this writing in January 2026 is open-sourced in the Circle Github repo. That code follows the same pattern as its predecessor: an authorized “blacklister” can freeze funds as before. But there is a difference in the deployment pattern: now the blacklister address is distinct from the minter. That does not imply they are different entities. It could just be a case of sound operational security to use different cryptographic keys to manage different functions. (Considering that the minting capability is far more sensitive and allows printing money out of thin-air, one would not want to use those keys for less-sensitive operations such as blacklisting.)

We can also observe on-chain how often that functionality is invoked by looking at all transactions originating from the blacklister. The record shows over 200 calls in the past year, of which:

- 170 are calls to blacklist

- 36 are calls to un-blacklist, that is lift the restrictions on a previously blacklisted address

Bottom line: This is not some hypothetical functionality lurking in the contract that is never exercised. Whoever holds the blacklisting capability for USDC has been routinely invoking that privilege as part of their oversight activities on the network.

Beyond blacklisting: Tether and asset seizures

Blacklisting an address prevents it from being able to move any funds, but is not the same as asset seizure. In the case of USDC, at worst funds can be indefinitely frozen and taken out of circulation. But they can not be reassigned to another party in response to a request from law enforcement. (At least not yet— recall that the proxy contract can be upgraded and Circle can introduce this additional capability in the future.)

Tether takes this one step further and allows direct seizure. Not only does it allow blacklisting, but there is an additional capability to reclaim funds after an address has been blacklisted. By following the implementation pointer from the current version, we can locate the responsible piece of logic. Excerpted here:

function destroyBlackFunds (address _blackListedUser) public onlyOwner { require(isBlackListed[_blackListedUser]); uint dirtyFunds = balanceOf(_blackListedUser); balances[_blackListedUser] = 0; _totalSupply -= dirtyFunds; DestroyedBlackFunds(_blackListedUser, dirtyFunds);}This code zeroes out the balance of the blacklisted address, removing the equivalent amount of tether from circulation. That may not look like asset seizure, in the sense that the funds have vanished entirely but that is illusory. Recall that tethers on-chain are supposed to be backed by actual US dollars in a bank account somewhere. (Although in the case of Tether, that has been notoriously difficult to verify due to the opaque nature of the operation and checkered history with regulators.) While the on-chain balances are gone, the US dollars are still sitting in the bank and free to be released to law enforcement or whoever initiated the seizure. If the authorities demanded to receive the funds in-kind, Tether could even execute a “mint” to magically have the equivalent amount appear at a specified address.

Postscript: breaking fungibility and censorship at the off-ramp

To be clear, this post is not intended to single out Circle and its compliance program. There is no evidence that either issuer has engaged in arbitrary asset seizure or randomly reversed transactions to settle scores with their competitors. By all accounts, every intervention was precipitated by a demand from law enforcement or financial regulator. For a US-based financial services company, that is the offer-you-can-not-refuse. Furthermore this functionality is not a “backdoor” or some hidden feature the stablecoin operator hoped to obfuscate. Contract implementations are open-source and every action to freeze/seize funds is visible on-chain, operating in plain daylight. In multiple cases issuers even boasted publicly about their commitment to compliance by highlighting specific instances of seizure they executed.

One would expect stablecoin issuers greatly prefer a hands-off approach to unauthorized transactions involving their asset. Hand-wringing and bromides on the theme of “code is law” are preferable to active intervention because the latter creates a lot of operational expense. In a high-interest environment, stablecoin issuance is extremely lucrative: all one needs to do is occasionally mint some large allocation of tokens when a wire transfer comes in from a handful of business partners, sit back to collect interest on those deposits and occasionally wire funds outbound when one of those partners wants to convert their stablecoin back into fiat. This business can be run with minimal operational overhead. By contrast staffing a compliance department and actively fielding requests from regulators around the world to promptly freeze criminal transactions takes a lot of work, eating into those enviable margins. (Compare that to the cost of resolving disputes in a credit-card network. No surprise stablecoin payments can be much more “efficient” than Visa/MasterCard when the former does not have to maintain 24/7 support to deal with fraudulent transactions or settle disputes between disgruntled card-holders and aggrieved merchants.) For that reason stablecoin operators left to their own devices would prefer to avoid engaging in outright asset seizure, censorship or transaction reversal, except to the extent that criminal activity becomes a reputational risk for the business. Yet the record makes it clear they have time and again staged such interventions. Even Tether, with its checkered history and popularity with organized crime groups behind pig-butchering scams, has recognized the necessity of responding to demands from regulators and seized funds on multiple occasions.

While the preceding discussion focused on direct censorship and asset seizure on chain, stablecoin issuers have another enforcement mechanism at their disposal. They can simply refuse to honor the convertibility of tokens back into real world assets.

Consider this hypothetical: some digital asset business is breached and crooks walk away with a stash of USDC stablecoin. Before Circle has an opportunity to intervene, the stolen funds are distributed to multiple addresses, exchanged into other currencies via decentralized exchanges or lending pools, maybe even bridged to other chains for USDC on Solana. There is no longer a single address where the proceeds of theft are concentrated, making seizure or freeze complicated. In fact some funds maybe sitting at a shared address such as a lending pool, mixed with other USDC contributions from honest participants in that pool. Clearly freezing the entire address out of USDC ecosystem is not an appropriate response in this situation. Even trying to manually adjust the balance by a careful sequence of burn/mint operations runs the risk that USDC will interfere with the operation of the pool. Case in point: prices on a decentralized exchange are determined algorithmically by an automated market maker (AMM) based on how much of the asset exists in the pool on both sides of the trade. Suddenly zeroing out the USDC balance can result in market disruption and wild pricing discrepancies.

A different way Circle can address this problem is by declaring that some fraction of USDC in the pool is permanently “tainted.” That USDC will no longer be considered as eligible for conversion back to ordinary US dollars, regardless of how many times it is transferred to other blockchain addresses. That last property requires Circle to maintain constant vigilance, watching for movement of tainted funds to other addresses and give them the same cold-shoulder if they ever show up demanding fiat dollars in exchange for their now worthless stablecoins. (This raises some thorny questions: which fraction exactly is tainted? If 1 USDC of stolen funds is added to an address containing 9 clean USDC and withdrawn in multiple chunks, how is the taint propagated? For technical reasons explorer in an earlier post, it turns out FIFO works better than LIFO for this purpose.)

By implication everyone else dealing in USDC must perform the same sleuthing— or more likely, outsource this process to a blockchain analytics service such as Elliptic or TRM. If Circle will treat some chunks of USDC as effectively worthless regardless of what the on-chain record says, everyone else is obliged to treat those tokens as worthless. This creates an insidious type of shadow-debanking: participants holding tainted stablecoins are free to transact and move those funds on-chain freely. But the moment they head for an off-ramp to convert those tokens to real-world dollars, they will discover their holdings are worthless. Those balances maintained in the USDC smart-contract ledger on chain turns out to be a chimera. If the only authoritative record— the ledger maintained by Circle compliance department— assigns a zero balance to an account, that account has exactly zero dollars.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.