[continued from part I]

A suboptimal heist?

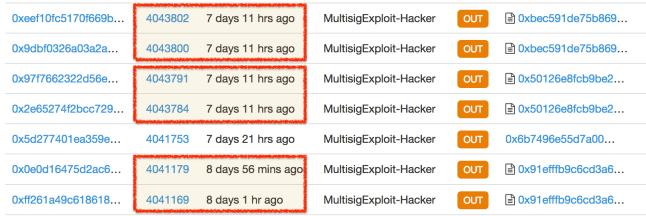

Looking at how the attacker exploited the vulnerability shows that it was far from being the most elegant operation. First notice the delays between the two calls made to each vulnerable contract. Here is another look at the pairs of calls made for exploiting three different vulnerable wallets:

Pairs of calls used to exploit the Parity multi-signature wallet vulnerability against three different contracts

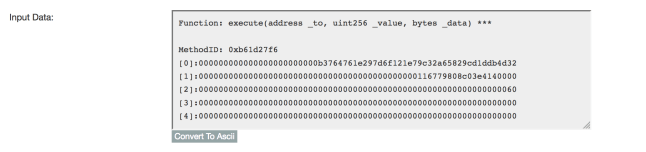

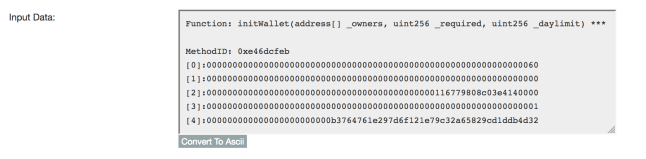

In the first attack, there is a gap of 10 Ethereum blocks between the calls, corresponding to ~3 minutes based on current block frequency. For the second attack, the calls are separated by 7 blocks. For the final victim, they are only 2 blocks apart suggesting that the perpetrator improved their execution over time. Still these wide gaps suggest that at least the first two attacks were being crafted manually, likely using an interactive REPL such as the geth Javascript console that allows invoking arbitrary methods on any contract. In principle there is no reason to wait between calls: as long as a miner processes them in the correct order, they could even take place in the same block. Even if the perpetrator is proceeding cautiously, waiting to confirm that the first step has achieved the intended effect, there is no reason to wait more than one block before pulling the trigger on the second one. (Note that unlike Bitcoin, Ethereum network does not have a perennial backlog of transactions or arbitrary fee hikes—unless an ICO is going on. Block timestamp is a close proxy for actual attacker moves.) In other words the attacker did not bother with automating the exploit by writing a script to make the calls in quick succession. Each victim appears to have been exploited with a hand-crafted sequence of calls.

That brings up the second mystery: choice of targets. The first successful attack is followed by several hours of inactivity, two more attacks in quick succession and finally, complete silence. There is more activity from the attacker address in days following the heist; but those are all for distributing the stolen Ether into other addresses, likely in preparation for cashing out. There are no other instances of the pair of calls to a vulnerable contract. While it is conceivable this actor switched accounts to better cover its tracks, there are no other instances of theft reported besides the original attack and the white-hat response. Assuming the white-hat group is indeed a distinct actor and not simply another front for the attacker, the surprising conclusion is the perpetrator operated on a leisurely schedule and stopped after targeting just three vulnerable contracts.

The next mystery is that 12 hour pause between the first and second attacks. That initial salvo netted a respectable 26793 ETH in spoils—over $5M. But the perpetrator was clearly not content to rest on those laurels, as evidenced by the following two encores. Why wait that long? Zero-day exploits have “half-lives,” especially when their affects are noisy; and it is difficult to imagine a more noisy demonstration of an exploit than burglarizing large sums on a public blockchain. Once the first vulnerable contract is hit, the clock starts ticking for everyone else to rediscover that vulnerability independently. In general such rediscovery poses two problems for the offense. First, other crooks will get into the game, racing the original finder to exploit remaining vulnerable targets. Second, defenders will be alerted to the existence of a vulnerability. They can craft a patch that closes the window of exploitation for everyone.

Granted that second response only applies if it is possible to upgrade an application in place without losing its state. While this is true for applications running on desktop and mobile platforms (you can patch your web-browser or operating system with nothing more than a couple minutes lost rebooting) it is not true for all platforms. For instance smart-card architectures compliant with the Global Platform standard have no concept of “upgrading” an existing application— applets can only be deleted and reinstalled, with all associated data lost in the process. (And that is a security feature: it protects applications from malicious updates, even by the software publisher.) It turns out Ethereum contracts are far more similar to smart-card applets than they are to vanilla Windows apps: Ethereum has no concept of replacing the code behind a contract with new code. In fact such a capability would run counter to the ideal of immutable contracts. If the code governing a contract can be modified after the fact, it can not be counted on to behave according to predefined rules in perpetuity. But all is not lost for the defenders: in an echo of the proverb “if you can’t beat them, join them,” white-hats can co-opt the exploit, using it preemptively to rescue funds from vulnerable contracts. This is exactly what happened during the DAO attack and again with the Parity wallet in this case.

Bottom line: once the existence of a vulnerability becomes public knowledge, the odds of successful exploitation for any one actor declines down over time. (Paradoxically the chances that any given vulnerable target will be exploited goes up; there are many more threat actors armed with the required capabilities. But they are all competing against each other for the same pool of victims.) A rational attacker being aware of these dynamics would pic off as many targets as possible in the shortest time to preempt the competition. Instead there is a 12 hour self-imposed ceasefire after the first successful exploit and only two more thefts after that. Why?

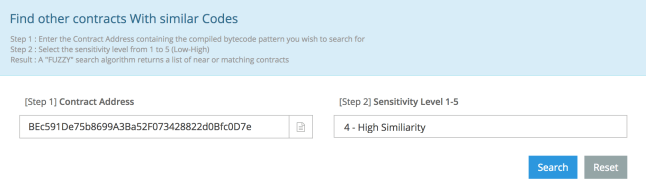

It is certainly not the difficulty of locating vulnerable contracts that is holding up the attacker. They have the exact same code; they are only differentiated by arguments to the constructor specified at creation time. That means a standard blockchain explorer can help locate other contracts sharing the same code. For example Etherscan has a web interface to search for similar contracts to one specified by address:

Locating contracts with identical or very similar code to a given contract

Given a security flaw in a widely used smart-contract, locating all instances of that vulnerable contract is shooting fish in a barrel. So why stop with three? The white-hat group has allegedly rescued 375K+ ether, more than twice the ~150K ETH the perpetrator managed to purloin. That is a lot of money left on the table.

Even more puzzling, the wallets attacked did not even represent those with highest balances. Given the increasing probability of rediscovery over time, the optimal strategy is going after wallets with highest balances first. But among contracts rescued by the white-hat group are three with balances of 120K, 56K and 47K respectively, each one alone higher than the take from the first victim. Why pass on these more lucrative targets when the same level of effort redirected elsewhere—doing nothing beyond copy/pasting a different contract address into the exploit sequence—could have yielded higher returns?

By all indications, the execution of this attack looks sloppy:

- No automation for delivering the exploit

- Long pause between the first and second wave, giving defenders precious time to organize a counter-strike

- Worst of all, suboptimal choice of victims that fails to maximize profit given complete freedom to choose targets

Yet viewed in another light, that last one may have been a deliberate decision to optimize for a different criteria: the chances of actually getting away with the theft, walking away with the ill-gotten-gains.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.