[continued from part II]

Assets and liabilities

Before delving into the options for proving that a cryptocurrency custodian has all customer funds in storage, a few word on what exactly we are trying to demonstrate. As before, there are individual customers who deposited varying amounts of cryptocurrency for safekeeping with the custodian. Those account balances are on the liabilities side of the accounting books— money owed to customers. They are tracked on an internal, private ledger maintained by the custodian. (For reasons explained earlier, the state of this ledger is not reflected on the public blockchain.) The custodian also controls some blockchain addresses where funds are logically kept; these are the assets. The objective is proving that custodian assets are approximately equal to its liabilities.

The fine print: time, currencies and drift

A few clarifications are in order. First, the comparison is always done at a specific point in time. Customer balances are in a state of constant flux: new deposits arriving, withdrawals leaving the wallet and at least in the case of exchange, trading activity resulting in funds changing hands among customers. To avoid discrepancies caused by such fluctuations, it is important to fix a reference time when answering questions such as “how much bitcoin does customer Alice have?” (This can get tricky for cryptocurrencies due to confirmation times: when the customer can sends bitcoin, there is usually a delay between those funds appearing in the custodian wallet and being credited to the customer. The former happens when the very first block containing that transaction is mined, while the latter may follow a few blocks later to allow for sufficient confirmation.)

Second, the comparison must be done independently for each cryptocurrency. In other words, bitcoin balances are reconciled on their own, independent of ether, litecoin or any other asset the custodian holds for that customer. The alternative is converting everything to notional dollar figure and only comparing totals. While that may appear to provide the same assurance regarding customer funds, it obscures important information. When a customer entrusts the custodian with 1 bitcoin, they expect the custodian to hold exactly 1 bitcoin and not that figure converted to equivalent amount of some other currency. Given the high volatility of cryptocurrencies, businesses engaged in that type of arbitrage activity would be exposed to risk from exchange rates moving in the wrong direction. Performing reconciliation independently for each supported currency demonstrates that no such conversions are taking place behind the scenes or necessary to satisfy customer liabilities.

Finally, why the qualifier “approximately” in the objective statement? Because there are at least two factors that can cause the numbers to diverge slightly in either direction:

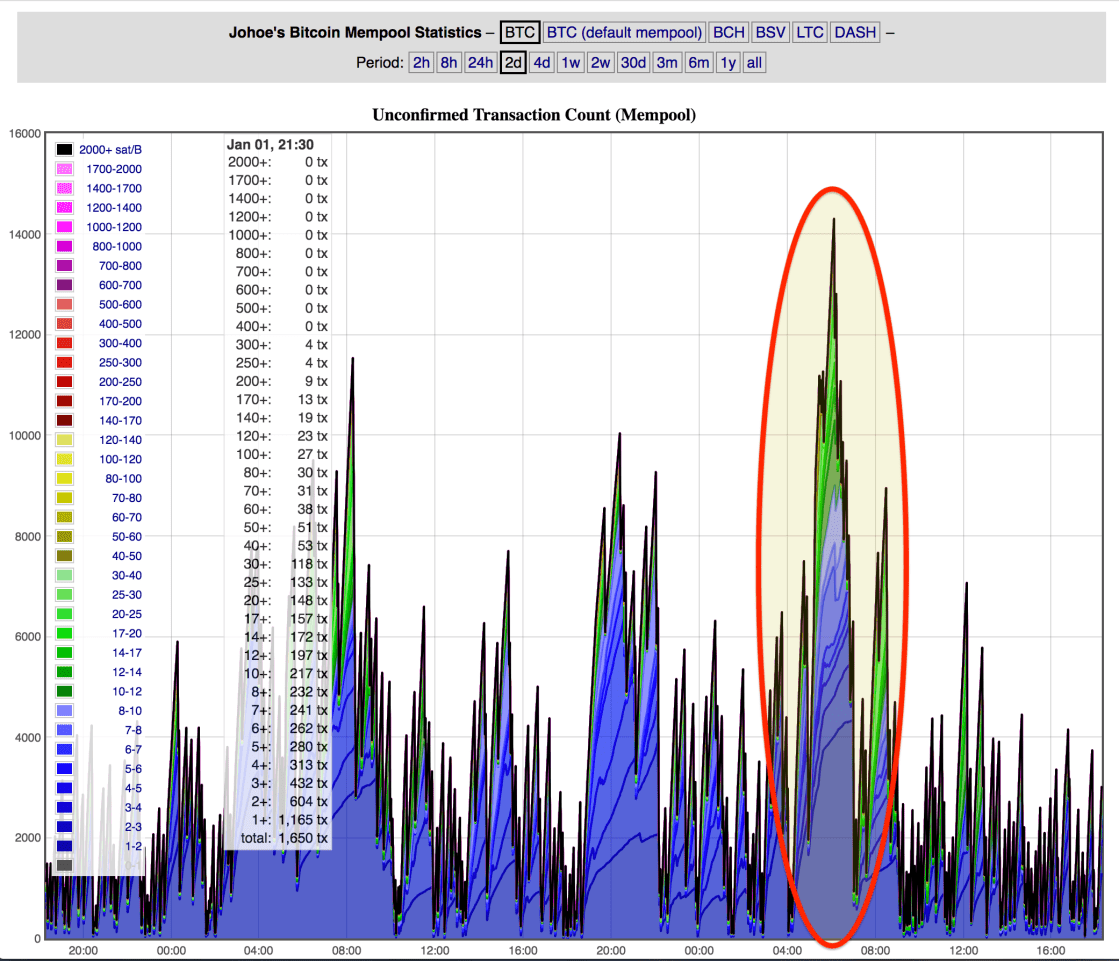

- Handling of fees. When customers withdraw, the custodian creates a transaction that includes not only the specific amount requested by the customer but also a transaction fee paid to miners for maintaining the blockchain. A “round-trip” of 1 bitcoin deposited and later withdrawn will draw on slightly more than 1 bitcoin in assets. (In case that sounds unfair, consider that the customer also had to pony up slightly more than 1 bitcoin on the way in.) Whether the fees are negligible or not in the grand scheme of things depends on several factors including blockchain congestion, transaction patterns and exchange rate. Recall one of the most counter-intuitive aspects of blockchain economics: mining fees are a function of blockchain space consumed by a transaction, not the value transferred. An inefficiently constructed 0.0001BTC transfer can cost more in fees than one sending 1000BTC. Many small withdrawals are worse than one withdrawal for the same total.

Depending on how the custodian accounts for fees— eating the cost, fully passing it on to the customer or something in between— it can result in a drift between assets and liabilities. In late 2017 when bitcoin fees spiked precipitously, many cryptocurrency businesses responded by adopting a less generous stance towards absorbing fees and cracking down on abusive withdrawal patterns. - Custodian business model. The way a custodian collects revenue for its services can also result in drift between blockchain assets and liabilities. Consider an exchange that allows trading bitcoin against ethereum. Typically both the buyer and seller are charged a commission as percentage of the value involved in the trade. If Alice sold 1 bitcoin in exchange for 40 ether from Bob, both Alice and Bob pay a commission to the exchange. (Not to be confused with mining fees, which are only relevant for transactions that hit the blockchain.) Which currency those commissions are charged in determines the direction blockchain balances could differ from ledger balances. Here is an over-simplified example: the exchange can treat Alice’s original offer as 0.999 bitcoin, charging her 10 basis points, while crediting Bob 0.998 bitcoin after settlement, charging him the same 10 basis points. As far as the internal ledger is concerned, the original 1BTC owned by Alice became 0.998BTC owned by Bob after the trade executed. Of course 0.002BTC did not vanish into thin air. It is still there on the blockchain— the only ground truth that matters for monetary value— associated with some address controlled by the exchange. But from an accounting perspective, it is no longer on the liabilities side of the ledger. The net effect is blockchain balances will exceed ledger balances over time, with the excess corresponding to revenue earned by the exchange.

I. Trusted third-party attestations

In this model, the custodian hires an independent party trusted by its customer base to perform the comparison of assets/liabilities and provide a written statement of their findings that can be shared with customers. The custodian is responsible for providing all necessary information required by the trusted third-party (TTP for short) to perform the comparison. In particular, they must be given access to:

- Snapshot of internal ledger at a predetermined point in time

- List of blockchain addresses used by the custodian at that same instant for each cryptocurrency

- Proof that those addresses are indeed controlled by the custodian (This proof can take different forms as described earlier.)

- If the custodian also deals in fiat currencies, access to bank statements or equivalent supporting documentation to verify those balances

If everything checks out, the third-party can provide a written statement to the effect that the custodian has demonstrated control over an amount of cryptocurrency equal to their outstanding liabilities. Everyone with access to that statement is free to form their own opinion regarding the assertions, based on their opinion of the author. Assuming a competent TTP with expertise in traditional accounting and cryptocurrency, this model has the advantage of following standard practices for proving the integrity of financial statements. It is common for management to bring in an impartial third-party to look over the accounting and perform additional due diligence to vet statements made by that management team about the financials of the company. While that third-party is faced with the challenge of carefully scrutinizing company records, for everyone else including customers, the problem is greatly simplified. They need only focus on the final outcome, the report stating whether that independent examination successfully verified statements made by the company.

What could go wrong with this approach in the case of cryptocurrency? There is the obvious element of trust in the entity performing the review. But assuming an honest TTP with stellar reputation, there is a more subtle element of trust in the custodian for correct execution of step #1 above.

The problem is TTP can not verify its version of ledger is identical to what individual customers are seeing. The custodian could tell Alice that her account balance is 10BTC while TTP is given a version of the ledger crediting her with only 9BTC. Short of reaching out to customers and asking what they expect their balance to have been at a particular time, TTP can not ascertain liabilities were captured accurately. Aside from sheer impracticality— have you ever received a call from the auditor of your FDIC-insured bank asking what you think your account balance ought to be?— this would raise serious privacy issues. Keep in mind that balancing the books does not require TTP to learn anything about the identity of individual account holders. Instead of using a real name such as “Alice” or “Acme Trading LLC” the ledger shared with TTP can represent customers with pseudonymous identifiers. (Of course even this leaks some information: for example if it is known that a given hedge-fund or high net-worth individual uses a particular custodian, their total balance may be gleamed from the pseudonymous data as the highest value.) Actually exposing the identity or contact information of customers to TTP is problematic.

Likewise even disclosing total assets under management as part of the attestation would not help reassure customers that their funds are accounted for. This is because only the custodian has a global view of liabilities across all customers. Individual customers only get a “local” picture of their own slice. For example they may receive periodic account statements or have a web page where they can view their balances. But short of collective action involving every single customer, they can not infer the expected total assets under management from their own balance. Consider a simplified scenario where the custodian only has two customers: Alice and Bob. Alice has 10BTC in her account. Suppose an accounting firm vouches for the fact that the custodian successfully demonstrated control of 15BTC on the blockchain. Does Alice get peace of mind? No because she has no idea of Bob’s balance or for that matter the existence of Bob. If Bob holds a balance of 5BTC or less, all is well. But if Bob also had 10BTC on deposit, there is a problem: each customer sees total AUM exceeding their own balance— a necessary but not sufficient condition— while total liabilities exceed total assets.

These limitations inspired a search for alternative models where customers can independently verify that their own funds are properly accounted for. One approach from 2015 using zero-knowledge proofs will be the subject of the next post.

CP

You must be logged in to post a comment.